Understanding early modern South Asia through Mughal warfare

Ashoka faculty uses new lens to explore Mughal history in his book

Office of PR & Communications

18 October, 2019 | 10 min read‘Doing historical research is like solving a crime as a detective.’

Can understanding the dynamics of Mughal warfare provide an insight into the processes that shaped South Asia? And, conversely, can it help understand how the South Asian environment influenced Mughal imperial expansion?

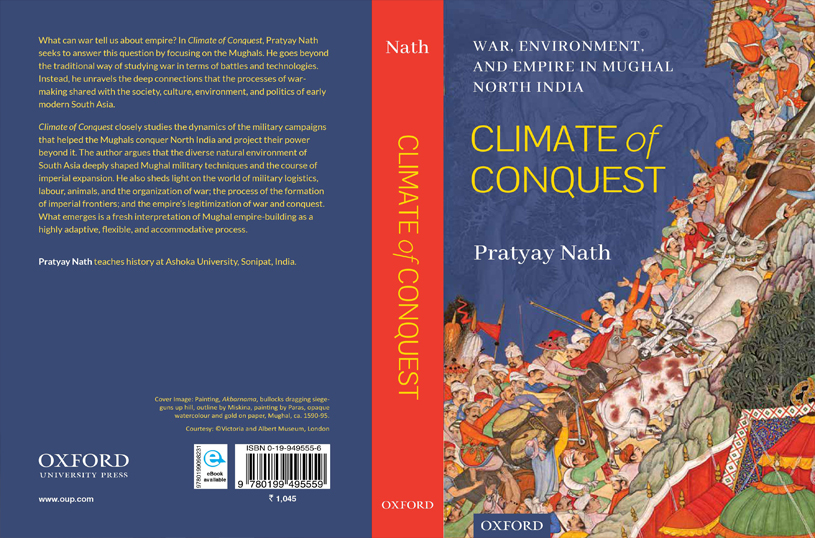

These questions and more led Pratyay Nath, Assistant Professor of History at Ashoka University, to unpack Mughal warfare through a fresh perspective in his new book ‘Climate of Conquest: War, Environment, and Empire in Mughal North India’ (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Below is an interview with the author, a historian of early modern war and empire, about his book, plans for future research, and whether he would like to indulge in writing historical fiction.

What is your book about?

The book is about the Mughal Empire. It offers a fresh interpretation of the process of Mughal empire-building by studying its interactions with warfare and the natural environment. The book addresses questions like how did the Mughal state think about war? What kind of logistical and managerial activities went into the making of military campaigns? How did the South Asian environment shape warfare and imperial expansion? In what ways did the state seek to harness environmental resources to fulfill its military needs? These are comparatively new questions for Mughal history.

In the process, the book weaves three separate fields together – imperial history, environmental history, and military history. It also compares Mughal war and empire with other contemporary processes beyond South Asia.

What inspired you to write a book on this subject?

Two factors. Firstly, sometimes we think that war is something very distant from regular social processes. That might be the case today for a large part of the world, but it has actually been quite the opposite for most of human history. War has generally been a very integral part of human societies. For the Mughals, for instance, military concerns shaped the very basic priorities of the state in a big way. War is not only about fighting. The state had to constantly gather thousands of animals for war; mobilise and pay soldiers; build forts, roads, and bridges; manufacture and transport arms and ammunition; and so on. All this kept the state perpetually busy. Even imperial ideology was moulded by how it thought about war and conquest. Because of its deep and constant investment in war, I realised that it is possible for us to learn a lot about the Mughal state and empire by studying its wars. It gives us a fresh perspective, because very few historians have attempted this so far.

Secondly, today we are very close to a global environmental catastrophe. There is a growing awareness about the human impact on the environment. At the same time, scholars are teaching us about how environment has shaped human societies. This is not only true for the modern times, but also for the premodern period. In this context, I realised that not too many historians have studied the interaction between Mughal empire-building and the natural environment of South Asia. As I studied Mughal texts, I found that there was, in fact, a very deep engagement between the two. On the one hand the empire constantly tried to mould nature for its own benefits. It built bridges across rivers, flattened the ground to make roads, and cleared forests to create flat open spaces. It used natural resources – like animals, food, and wood – to supply its armies. On the other hand, nature too shaped the empire. In Bengal and Assam, rains, rivers, and floods jeopardised military campaigns repeatedly. Similarly, the cold weather, snowfall, and aridity of Kashmir, Balkh, and Qandahar made war-making difficult. This was one of the main reasons for Mughal imperial expansion faltering and halting in these regions. This history needs to be told.

“Doing historical research is like solving a crime as a detective. A detective reaches the crime scene when the crime has already happened. She tries to recover whatever clues she finds, studies them critically, and tries to recreate the crime as it took place. Similarly, the historian goes through the remnants (‘sources’) of the past and tries to put together a picture of a past she has never seen. Sometimes pieces of information are missing, certain details cannot be ascertained for sure. These are difficulties that all historians face. I was no exception.”

What kind of challenges did you face in writing this book?

Recreating and explaining something that happened hundreds of years back is not easy. The only guide I had here were Mughal, European, and vernacular texts. This also brought linguistic challenges. I mainly worked with Persian, English, Bengali, and Assamese languages. Still, I did not always find the information I was looking for. Sometimes there is only one source for an event and it was difficult to ascertain what exactly happened based on that one source. At other times, the nature of a source is such that it reveals certain kinds of information and hides others. However, consulting multiple kinds of sources helped me negotiate these challenges. In the end, I was able to put together a more or less cogent analysis of my subject.

Would you like to talk a little about your current and future projects?

I am currently working on a book on Akbar’s wars. Akbar was a remarkable ruler and his reign has received a lot of attention from historians. Yet, very few have worked on the actual process through which Mughal armies conquered a very large part of South Asia. I want to study this history in terms of military tactics, strategies, and logistics. I also want to understand how the Mughals would tackle rebellions and insurgencies in different regions and then how they would gradually move from military conquest to administrative control.

Alongside this, I am co-editing two collections of essays. The first emerged out of a conference organised by the History Department, Ashoka University, last year. Here a group of ten historians – including myself – are critically looking at the category of ‘early modernity’, which is used now to designate the time period loosely between 1500 CE and 1800 CE. This is something relatively new, because earlier this was considered to be a part of the ‘medieval’ period. We work on various fields – religion, environment, warfare, trade, and so on. Each of us is thinking about how this category of ‘early modernity’ applies to our individual fields. Together, the volume asks, what does ‘early modernity’ mean in South Asian history? Is it just another name to designate a time period, or does it also encompass specific historical processes in the different fields mentioned above?

The second is a volume in Bengali. Here we have twelve historians looking at twelve big debates of Indian history. These include the Aryan debate, the feudalism debate, the eighteenth century debate, and so on. We are studying how academic debates in these individual fields have evolved over the course of the last century or so. We are asking why are these topics so fervently debated? Do debates exist because new historians look at new historical sources, or because they read the old sources in new ways? How do the social and political tendencies of the historian’s own times shape the history she writes? So in a way, this volume is an analysis of the processes of history-writing on South Asia.

How is it to write history in Bengali, given that your primary professional language is English?

The main concern for us in the Bengali volume is to reach out to a Bengali-medium readership. This comprises students and teachers who lack our social privilege of English-medium education and mainly study or teach in Bengali. Our aim is to bring the latest historical knowledge to them in their preferred language. However, the task is really challenging, not only for me but for all the authors of this volume. For us, the language of higher education has always been English. Since the very moment that we started thinking about history seriously, we have thought and written in English. Hence making the shift to thinking and writing history in Bengali has not been easy. Often we struggle to find expressions and technical terms in Bengali while writing. However, all of us are deeply invested in this and determined to overcome these obstacles. Two things help. Firstly, we often brainstorm collectively, read each other’s writing, and provide feedback. Secondly, there is a very rich corpus of existing historical works in Bengali that we can fall back upon.

Last question. Have you ever considered writing historical fiction, given how popular it is these days?

Yes, it is true that a lot of very interesting historical fiction has been published recently. Several non-historians are also writing history for a general readership. All of this has made history a topic of conversation and debate in our societies. These books are often written in very lucid language and around curious anecdotes. Much more than academic historical works, these books recreate a lost world for a general readership in interesting ways. I would like to add that certain computer games – like Mafia, Total War, and Company of Heroes – also do this. However, my training in the discipline of history encourages me to engage with the past more critically, using the rigorous and painstaking methods of academic research, and say nothing that does not emerge from an analysis of actual historical sources. Hence I have no plans of writing historical fiction or non-academic histories in the near future.