‘We are still in the closet in our thinking about desire’

Madhavi Menon opens up on her just-published book “The Law of Desire” in this freewheeling interview, maintaining that the law pretends it is based on truth even as it reflects social prejudices and phobias

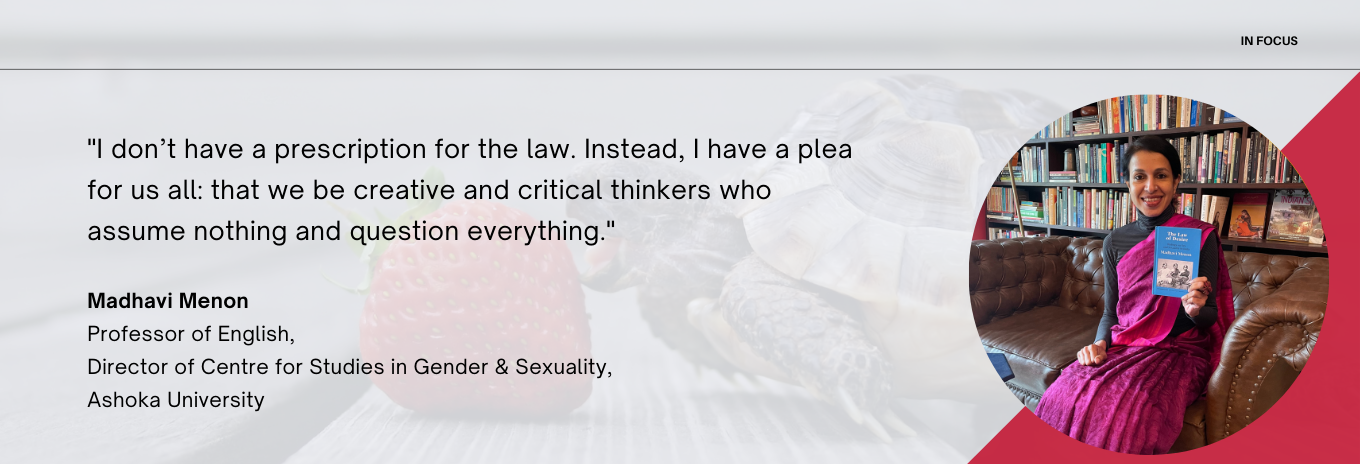

Ashoka Professor of English and noted queer theorist Madhavi Menon has always been interested in the law. Her latest book, The Law of Desire: Rulings on Sex and Sexuality in India, has just arrived on the stands with rave reviews from leading newspapers and magazines. Published by Speaking Tiger, the offering presents the many ‘conundrums and paradoxes’ that result when the law is entangled with sex and sexuality.

A go-to guide for everybody interested in gender, desire, sexuality and obscenity and how the Indian judiciary has reacted to it over time, the book is up for grabs at leading bookstores across India and e-commerce platforms.

We sat down with Professor Menon, who is also the Director of the Centre for Studies in Gender & Sexuality at Ashoka University, to understand her motivation behind writing this book as well as to assess the key arguments that she has put forth in this timely offering. In her responses to some specific questions pertaining to her book and a few rhetorical ones, Professor Menon provides an overview of her book and is unflinching in calling a spade a spade, contending that like many judiciaries and legal systems around the world, India’s too is steeped in misogyny and sex-phobia.

Excerpts from an interview:

What is your motivation behind writing The Law of Desire? How did this process begin and can you take us through the journey of writing this book?

I have always been interested in the law. As the overarching structure within which we live our daily lives, the law affects us on both micro and macro levels. Law is both upper-case and lower-case: social laws both produce the Law and are produced by them. Does a change in the Law trickle down to changes in social and sexual laws? Is law ~ both lower- and upper-case ~ only restrictive or does it also create spaces for flourishing? Does restriction enable desire to thrive instead of only thwarting it? These are some of the questions I was interested in exploring in The Law of Desire. Despite the use of the definite article “the” and the upper-case “Law” in the title, I explore the ways in which law is always multiple and capable of different interpretations. It can neither define nor be defined with universal precision.

The blurb of the book asserts that we need to play with, rather than stay with, the Law of Desire. Are you suggesting that we need to introspect and reevaluate the laws that seem to govern desire in our society?

The book suggests that both law and desire have a fundamental relationship with plurality rather than singularity. This means that both law and desire preside over realms that are too multiple to be fathomed in any one way alone. But the difference between the law and desire is that law has aggrandised itself to such an extent over the centuries that it now believes itself to be The Truth. All the language surrounding the law is steeped in the absoluteness of religion ~ you “pray” to the Court, judges are called “Your Lordship” (even when they’re women), and you can be held in “contempt” of court for criticising it. Law attempts to place itself above the realm of the common, on a perch from which it can direct the ways in which people should live and list the punishments that will accrue to them if they do not live in that prescribed manner. And when it comes to desire ~ even in cases where there is no victim, as in the case with homosexual or trans* desire ~ the law prescribes what people should and should not do, and where they should or should not do it. This is where law and desire are most at odds, with the former trying to squeeze multiplicity into a one-size-fits-all paradigm. But this attempt to squeeze can also be pleasurable, and desire has historically found ways of getting around the vice-like grip of the law.

What is your evaluation of the judiciary’s handling of gender, sexuality and obscenity in India?

Like many judiciaries and legal systems around the world, ours too is steeped in misogyny and sex-phobia. This means that no matter how progressive an individual judgment might seem to be, it continues to depend on ideas of sex that are closely attached to shame. Thus, the wonderful 2018 Supreme Court judgment on Section 377, for instance, which decriminalised “carnal acts against the order of nature,” nonetheless continues to think of sex as something that should only happen in private. Whether criminal or not, then, we are still in the closet in terms of how we think about desire and its “proper” realm. As for obscenity, this is famously the legal realm that lacks all definitional precision. What is obscene for one person is not so for another, and this is true also for judges. Different judges look at the same piece of art or literature differently, and rule accordingly. Obscenity might mark the limit of the law’s narrative about its own clarity and objectivity.

Is it necessary to ensure heterosexuality in our society?

If this were a face-to-face interview, then I would laugh at this point! It is so delicious, isn’t it, to think that something we consider “normal” and “natural” might actually be legally mandated and reinforced? But I do think that is the case. In an overwhelming confluence between big Laws and small ones, heterosexuality is socially-procreated and legally protected. Every child is assumed and then encouraged to be heterosexual, just as many laws are premised on a husband and wife unit. What makes this heterosexism delicious, though, is the fact that if heterosexuality really were “natural,” then surely it would not need to be mandated, and people would not need to be encouraged to move in its direction? This is a good example of how the law pretends that only one desire is natural even and especially when it is faced with multiple versions of desire.

From where does desire gain its legitimacy? Is it dependent on the law to approve of its existence or is it a natural process that needs no hindrance from the law?

As my previous answer suggests, I am very wary of using the word “natural” to describe any aspect of desire. Doing so immediately opens us up to judgments about desires that are “unnatural. After all, what is deemed “natural” needs to be pitted against something that is deemed to be its opposite. But at this moment in our history, we carelessly equate what is legal with what is natural, without thinking for a minute about the contingent status of both these categories. Even further, we equate what is legal with what is natural with what is good. Thus, different people want their sexual desires to be validated by the law in order to feel good about themselves. To my mind, such dependence on the law to validate one’s desire and one’s being sets a dangerous precedent. It allows the law to categorise neatly what can only be understood and experienced as the messiness of desire. We then start to feel like our desire too should be neat, legal, and natural rather than unruly, but it never can be, and so that becomes a source of tension for us. I think it’s time that we start to enjoy messiness rather than categorisation as the hallmark of desire. This would mean that instead of rushing to the law to have our desire “recognised,” we should bring the law to its limit, where it is faced with its own incoherence. For instance, “carnal acts against the order of nature” has been interpreted legally to mean non-reproductive sex. This class of sex acts covers all sexual orientations even as the law has settled it narrowly on homosexuality. Instead of rushing to legitimate homosexuality, then, we should insist that heterosexuality too is, within this definition, illegal.

Tell us about one major judgment around desire that you think was not necessary?

There are so many! But the Hadiya judgment, to take one fairly recent example, is something that I consider not just unnecessary, but also pernicious. I have written about this case in detail in The Law of Desire, but for now, suffice it to say that this case showcased the most misogynistic and communal strands of thinking that seem rampant in the legal system in our country. The Kerala High Court in 2017 dissolved the marriage of Hadiya and Shafin Jahan because Hadiya’s father said she was a young and impressionable girl and should be under her father’s care rather than being allowed to choose what religion to follow and who to marry. Shockingly, the Court agreed with this paternalistic argument despite the fact that Hadiya was then a 24-year-old adult. The Supreme Court overturned this ruling in 2018, though it allowed the NIA to investigate Shafin Jahan based on the spurious allegations of Hadiya’s father. The NIA found no grounds to prosecute Shafin Jahan, but the conviction of a Muslim man’s criminality and women’s unreliability in matters of desire is an old trope that te law never seems to tire of. Indeed, it seems to have got a fresh lease on life with the insidious political insistence on “love jihad,” where the woman is too foolish to know her own desires and therefore needs to be “protected” by the pater and the paternalistic law.

Going forward, what is your prescription for improving the laws that seem to be built on very weak and often casteist and patriarchal assumptions?

I am not sure I have a prescription for the law. Instead I have a plea for us all: that we be creative and critical thinkers who assume nothing and question everything. The law pretends it is based on truth, but it reflects the worst phobias that plague our society. Lawyers were once upon a time great intellectuals and radicals ~ that is why they were able to lead India to independence from the British ~ but now they seem increasingly politically corrupt and intellectually moribund. Perhaps they need a liberal arts education at Ashoka in order to understand that the law requires more flexibility and imagination? The fear, though, is that then it will no longer remain the law.

(Written by Saket Suman)