#Bookmarked: Of selective remembrance and suitable memories

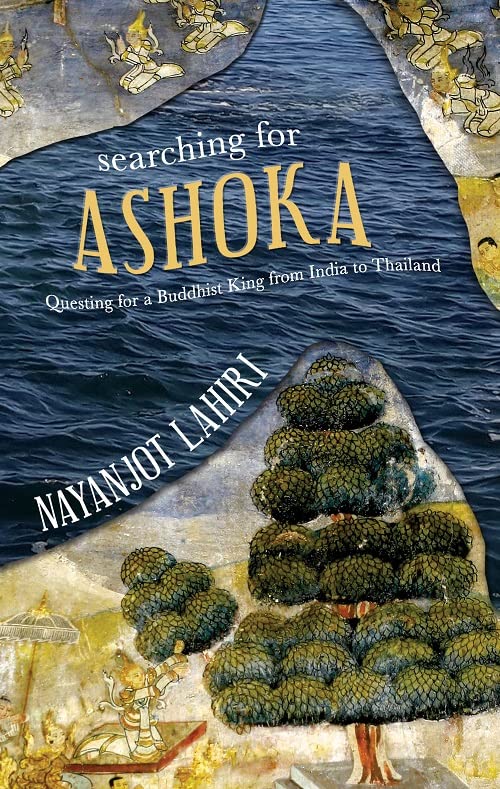

Nayanjot Lahiri’s book ‘Searching for Ashoka: Questing for a Buddhist King from India to Thailand’ published by Permanent Black (and to be published by SUNY Press in March next year) explores how Ashoka, the famous emperor of ancient India has been remembered, forgotten, and recast over time

Saman Waheed

28 November, 2022 | 6m readNayanjot Lahiri is a Professor of History and a member of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Archaeological Research at Ashoka University.

Her latest book, “Searching for Ashoka” blends travelogue, history, and archaeology, to unravel the various avatars of Emperor Ashoka. Through personal journeys that take her across India, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Thailand, Nayanjot Lahiri explores how Ashoka’s visibility from antiquity to the modern era has been accompanied by a reinvention of his persona.

We spoke to Professor Lahiri about the years she spent in the company of Emperor Ashoka and how this book came to be. Here is what she had to say.

Out of all the historical figures, what made you choose Ashoka? Is there a specific reason behind it?

There have been some 2000 publications on Ashoka. All the big scholars of ancient India have written about him at some point in their lives. He really was the most well-known emperor of ancient India. So, when I got the opportunity, facilitated by Harvard University Press, I thought it to be the right time to engage with him. So, I did this book on the historical Ashoka titled Ashoka in the Ancient India, studying his edicts carefully to work out his life trajectory, travelled to where his edicts were from and looked at the archeology around that, and then built up that narrative.

Ashoka was a third-century BC emperor with a very large imprint not limited to India. I travelled around many places where his words can be found, to realise that over time, there were ways in which his words and their surroundings have a long-term history that was somewhat different from what Emperor Ashoka was all about. As I was finishing this book while at the University of Delhi, I put in a concluding chapter with the idea that there is a book waiting to be written on the remembrance of Emperor Ashoka.

I, then, joined Ashoka University, where the faculty is provided an annual grant to work on their research. So, I thought to myself, why not travel again, searching for this Ashoka who is remembered in so many different ways? That is how this particular book, Searching for Ashoka came about. So, I did not just travel to India, but to Myanmar, Thailand, and Sri Lanka as well to look at memory not only in relation to Ashoka but also for myself to understand how memory works, and how memory is very different from history actually.

This was my first academic engagement in that sense with lands beyond the Indian subcontinent. My travels in these countries about which I knew little, helped me become less insular as a scholar. I now have some working knowledge about the ancient, medieval, and early modern histories of those nation-states and I have to thank Emperor Ashoka for being the spur that led to that education.

This book discusses selective memory- remembering and forgetting what Ashoka and his ideas were all about. Could you please elaborate on the same?

The first thing that struck me when I read the edicts of Ashoka which I also discuss in the introduction to this book, is that memory also figures in the Ashokan edicts. I began by asking myself the question—what did Ashoka remember and what did he forget? Whatever he remembered was, in fact, a very selective recall. He remembered earlier times, in order to make his own engagement with the present burnish. He saw the changes he made, the morality and the dhamma that he introduced, and the conversion of people to that idea, in relation to an earlier time, so the earlier times always looked much worse than the present. He talks about his immediate past when he moved to Buddhism and how that had made him and his kingdom a better place. Every time memory figures, Ashoka wants the present to appear as a watershed and very different from a less glorious and problematic past.

The second thing was to see what constituted the historical Ashoka and how different the remembered Ashoka was. If you look at the historical Ashoka, there is an emperor who is an unusual thinker with unique ideas of governance. He was the only ruler who put up his words in places where people lived and worshipped and along the routes they travelled to. He talks a lot about his own methods of disseminating his ideas, about a spiritual and novel form of governance, and also the way you should govern yourself and your own emotions. This is one avatar of Ashoka.

The other avatar was the ruler who moved towards Buddhism, which he mentions in his first verse. Over time, his words can also be found in places that are associated with Buddhism. At Lumbini, Emperor Ashoka put up a pillar with words that indicate that he reduced the taxes because this was the place where the Buddha was born. He also appears to the Buddhist Sangha as an equivalent of the papal figure in Christianity, where he tells them that there should be no schisms within the Buddhist monastic community, those who are schismatics will be turned out, and which teachings of the Buddha they should focus on.

There are two types of Ashoka that figure in his words, but the Ashoka that is remembered is his Buddhist avatar. This Ashoka who captured my imagination because of his unique ideas of governance does not figure.

In southeast Asia, Ashoka is not remembered as a ruler with a completely distinct way of looking at the political system. He is remembered as the archetypal Buddhist king. He is memorialized by many dynasties in southeast Asia with Buddhist rulers who link themselves with Ashoka to showcase that their land has had a long engagement with Ashoka.

In Sri Lanka, he is remembered more through his children. His son Mahinda brought the Sri Lankan king Devanampiya Tissa into the Buddhist fold while his daughter Sanghamitta sailed on a boat carrying a branch of the Bodhi Tree and converted the queen (Devanampiya’s wife) into Buddhism. This story assumes a huge significance beyond India and Sri Lanka. It is depicted on the cover of my book where Emperor Ashoka is taking the southern branch of the Bodhi tree to give to Sanghamitta, who is going to cross the ocean to go to Sri Lanka.

In history books taught in school, Ashoka is presented first as a ruthless warrior and then as a Buddhist spiritualist. How right or wrong is that, in your opinion?

It is, of course, a very black-and-white representation which is not necessarily the way Emperor Ashoka was. I do think there was a ruthless streak to him that remained throughout his life. It was very much a part of the way he captured the throne. He was not the eldest son of his father and he snatched the throne. That may be one of the reasons why the lineage of Ashoka never figures in his words.

He also must have been a king very much in the Arthashastra mold because he himself tells us in his 13th Rock Edict that he conquered Kalinga. Ashoka was the third ruler of the Maurya empire which was created in the time of his grandfather. He did not conquer any other parts of India except Kalinga. His words make it clear that it was a very bloody conquest because thousands of people were killed, enslaved, and suffered in various ways. There must have been a very strong resistance to Ashoka taking over Kalinga. I think coming face to face with so much death and decimation, at his own hands must have led to deep anguish and turmoil. He then decided to become much more pacifist.

In my interpretation, the credit for his conversion to Buddhism goes to Devi, the great love of his life and also the mother of Sanghamitta and Mahinda. She was a Buddhist. They had met when he was a prince, and they soon became a couple. This is not there in the books, because you do not find women being given credit. However, the Buddhist who is the closest to Emperor Ashoka has to be Devi.

In the 13th Rock Edict, where he talks about his remorse after Kalinga, he also says that all these unconquered borderers like the atavikas (foresters) should learn from his example. If they do not, then he has the power to conquer them. In this way, he follows a carrot and sticks policy, where one can either have a change of heart and become like him or can face the extent of his force.

Therefore, this idea that Emperor Ashoka gave up his army is not true. He very much had the power of his armed forces, which was invoked against people who were not very comfortable with his rule or following his policies. The ruthless streak is definitely there and it is articulated by Ashoka himself. This is why I believe that the picture of Ashoka imparted to students often does not convey the whole truth.

What would you say is the contemporary relevance of Ashoka’s ideas on politics, governance, religion, and spirituality?

I do think there is a significant contemporary relevance because of his novel ideas of governance, articulated by his edicts. He may have been a Buddhist but he also created beautiful, polished granite caves for the Ajivikas, who were a very powerful ascetic sect. He also talked about respect and liberality towards the Brahmins. He also said that one should never praise their own religion publicly in a way that seems to put other religions down. He talked about a world where all communities and sects live together. In the India of today, I think these are very pertinent ideas.

Without an environmental crisis, Emperor Ashoka was the first to talk about compassion towards all living beings. When the articulation of his foreign policy is examined, we see that he is trying to plant trees, and set up hospices for the medical treatment of animals and humans in other lands. So, for him, human beings are not the only ones who matter. He tells his people to not kill pregnant animals, to regulate their castration, and a great deal else.

Is there anything else about the book that you would like readers to know?

It is as much about contemporary times as it is about the ancient world. When I talk about the image of Emperor Ashoka being created on a panel with his queen at Kanaganahalli in Karnataka, I also talk about what has happened to that panel at the hands of the Archaeological Survey of India. When I talk about the Barabar Caves that were largely used by Ajivikas, the creation of the caves, the fading of the Ajivika identity, and the evolution of the cave into a Vaishnava shrine are also a part of the story. So, there is as much about the ancient as there is about the medieval and modern.

I imagine that readers will be surprised to find out that the image of Ashoka is very bright in places in Southeast Asia such as Myanmar and Thailand, which he never engaged with. Yet, it is a very different image. It is a very different kind of Ashoka from the historical Ashoka that we know. Remembrance is very different from what actually happens in history and forgetting is as much a part of remembrance, so, it is essentially selective remembrance.

Lastly, I hope the readers enjoy the book.

(Saman Waheed is currently an Assistant Manager at the Office of PR & Communications, Ashoka University. She is a former Young India Fellow from the batch of 2022.)