Ecology and German Realism: In Conversation with Professor Alexander Phillips

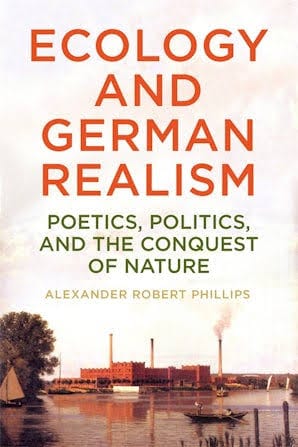

Professor Alexander Phillips, Assistant Professor of English, Director of the MA programme at Ashoka University, talks about his recently published book: Ecology and German Realism: Poetics, Politics, and the Conquest of Nature. He reflects upon his journey of writing this book, his research quests along the way, the challenges he encountered, and how the University environment contributed towards bringing his vision into reality.

In an in-depth conversation with the Research and Development Office, Professor Alexander Phillips, Assistant Professor of English, Director of the MA programme at Ashoka University, talks about his recently published book: Ecology and German Realism: Poetics, Politics, and the Conquest of Nature (Studies in German Literature, Linguistics and Culture Book 251).

During this conversation, Professor Phillips reflects upon his journey of writing this book, his research quests along the way and shares key learnings and insights. He also delves into the challenges he encountered and highlights how the University environment contributed towards bringing his vision into reality.

Introduce us to your book, Ecology and German Realism. What is that one central question your book is aiming to address?

Ecology and German Realism explores the topic of environmental degradation in the works of four major German-language authors active between 1840 and 1900: Adalbert Stifter, Wilhelm Raabe, Theodor Storm, and Theodor Fontane. These were the years when Germany became a unified country for the first time in history, and that allowed for rapid industrial expansion, utterly changing the land and cityscapes over the course of the authors’ lifetimes.

Scholars have long pointed out that German realist authors seldom depict urban and industrial life in the way that, say, Charles Dickens did, preferring more rural settings instead. But in those rural environments we see, for instance, early industrial agriculture, as in Adalbert Stifter’s novella Brigitta (1843/47), pollution in Wilhelm Raabe’s novels, or even the industrial glassworks near the idyllic country estate in Theodor Fontane’s The Stechlin (1898). I wanted to understand the environmental politics at work in these novels, especially because none of the authors would have understood themselves as “environmentalist” in the way we use the term today.

However, I also wanted to understand what the environmental themes meant for the novels as works of literature. Realist literature claims to represent the world, however fictionalised, but we are still talking about works of literary art. And for these authors, the ugliness of industrial modernity is a big problem for representing the world aesthetically.

Your book brings together two interdisciplinary fields. What was the key moment in your research that directed you towards the idea that there was a deep connection between the environmental degradation of the 19th century and German Realist aesthetics?

It is hard to identify one key “ah-ha!” moment that directed me towards the connection. Instead, it was more a process of noticing patterns within and between the stories that further reading, writing, and re-rewriting brought into focus.

One key moment may have been when I first read Theodor Storm’s The Rider on the White Horse (1888), about a dike project that creates arable land from a wild open sea, which the text associates with ghosts, mermaids, and giants. When I first read the story as a beginning German literature student, I wondered how a story could contain such elements and still be considered “realist.” As it happens, the dike itself parallels the claims that literary realism makes, because in the story, creating a boundary between wild nature and the mythic beings associated with it mirrors the boundary realism draws between the everyday and the fantastic, the apparent paradox being that the novella leaves open the possibility that ghosts, mermaids, and giants are also “real.”

Another key moment was reading Wilhelm Raabe’s Pfister’s Mill, in which the poet character delivers an apocalyptic poem about a “mighty dust cloud” sweeping away the bourgeois world before he himself gets drunk and drowns in the polluted river. What did it mean for the novel to drown poetry in an industrial cesspool symbolically, I wondered?

Meanwhile, off the page, my own outdoor activities have yielded valuable insights. I happen to be a long-distance endurance cyclist, and long days in the saddle mean plenty of time to think about my own aesthetic encounters with the landscapes around me, be they through vineyards on the Rhine or the coalfields of southern Maharashtra and northern Telangana.

Could you walk us through your research journey? What research methodology did you use? Which texts, archival materials, and primary sources were examined in the writing of your book, Ecology and German Realism?

The environmental dimension of the stories I cover stood out to me already as an undergraduate, when I was first reading around in the literature of the period. I remember reading Theodor Fontane’s Effi Briest (1895) for the first time and being struck by a comment Effi’s friend Frau Zwicker makes that there is no longer any difference between Berlin and Charlottenburg, referring to how Berlin has sprawled out so much that it physically encompasses previously independent cities, turning them into mere neighbourhoods.

It is a fleeting comment that appears only in parentheses. Still, it struck me particularly because I spent my adolescence in one of the neighbourhoods that represents the very worst of urban sprawl in the United States since World War II. Later, as a graduate student, when I saw urban sprawl and its environmental effects more consistently thematised in Wilhelm Raabe’s The Birdsong Papers (1896), I realised that not only was urban sprawl something that the authors thematised, but it was part of a larger pattern of thinking about how abstract social and economic transformations were reflected physically in the land.

I had the opportunity to conduct research in the City Archive and visit the Literaturzentrum in Wilhelm Raabe’s former house in Braunschweig, as well as the Stadtmuseum in Berlin and the Theodor Fontane Archive in Potsdam. I am grateful to the staff there who conserve these materials and make them accessible.

Your book examines how 19th-century German literature engaged with environmental changes happening around that time. It would be interesting to understand the following:

In what ways do the insights from history and literature contribute to the understanding of the current global landscape of climate change?

An axiom of environmentalism is that ecological crisis is also a cultural crisis. That cultural crisis encompasses, among other things, our desires for carbon-intensive lifestyles, our foodways, and our very concepts of nature. Literary texts are documents of culture, and in the case of historical authors such as Stifter, Raabe, Storm, and Fontane, we can get a perspective on the longer processes that brought us to where we are now.

Sometimes that can entail moments of familiarity, like the surprise I felt discovering that nineteenth-century fiction was already working through problems like pollution or urban sprawl that I was seeing in the twenty-first. But more helpful, to my mind, are the differences, seeing how other people in other times and places conceived of and represented their experiences.

In the case of climate change, addressing the problem means rethinking our assumptions about reality and ways of being in the world. Revisiting historical works of literature can help us realise that our current world is not the only one possible and that other people have lived their lives in different ways.

How do these insights from the 19th century shape our understanding of the role of the humanities in the current environmental movements?

Effective political movements should not just understand the origins of the problems they seek to address, but also be self-aware enough to have a sense of their own histories. As it happens, the authors I work with were writing at a pivotal moment for the emergence of modern environmentalism.

The very term “ecology” comes from the German “Ökologie,” and was coined by Ernst Haeckel, one of the most prominent proponents of Darwinian theory, in 1866. When it comes to the texts that I deal with specifically, they thematise environmental degradation and have a pronounced critical edge, but they are hardly activist. They do not necessarily condemn the environmental degradation they depict. Many of the characters in the stories instead see it as an unfortunate but inevitable development as the world turns. That has led some scholars to question whether we should even think of them as “environmental texts.”

My book shows that there are more complicated dynamics at work in the stories, but even if the texts stop short of condemning environmental degradation, they are still valuable, for they show how an environmental concern, if not an environmental politics, can fit as comfortably on the conservative right as on the political left. Environmentally concerned people today would do well to understand that, and indeed, we see many on the global right rediscovering aspects of environmentalism for themselves.

What were the key challenges you encountered while writing this book, and how did you address them?

The biggest challenge was one that any researcher grappling with a problem in culture faces, that of simply finding a language for talking about a given problem. “Nature” is a complex word. It carries with it all manner of ideological sedimentation, especially when it connotes normativity and is used as a rhetorical cudgel against those who do not comply. It also means different things in different cultures and reflects different histories. Much of the first ecocritical theory I read was developed out of studies of American nature writing, and so it seemed to be a poor fit for Germany, most of which had been deforested by the High Middle Ages.

How do you see your book resonating with a wider audience? In what ways can it contribute to the betterment of society?

I would like my readers to appreciate the works as part of a larger transhistorical and transnational conversation about the state of the environment and the representation of nature in letters, and so I hope that the audience walks away with a deeper understanding of the aesthetic dimension of ecology and the ecological dimension of aesthetics.

The book situates Stifter, Raabe, Storm, and Fontane within a longer history of debate on the representation of nature that includes other works of nineteenth-century fiction, including such canonical works as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), and continues down through authors like Edward Abbey, Annie Dillard, and on to contemporary debates in ecocritical theory. What that means for readers as individuals who might have their own ideas about social betterment is up to them.

If nothing else, I hope that English-language readers will feel moved to explore the authors I write about for themselves.

What new research projects are you working on?

At the moment, I am developing an article on environmental ethics in Marlen Haushofer’s 1963 novel The Wall. The story is a post-apocalyptic story about a woman who goes on vacation in the Alps, then wakes up one day to find an invisible wall has descended on the landscape, leaving her apparently the only person left alive. She reflects on matters such as the care she gives to her animals, as well as the limits thereof, the value of understanding natural history, and the freedom she enjoys without any men around.

I am also doing preliminary work on my next book project, which will be on the topic of climate and the aesthetics of atmosphere in the literature of the hydrocarbon age.

What interests the researcher in you?

I often find myself thinking through the relation between the material world and more abstract cultural problems. In Ecology and German Realism, the problem is the physical reality of environmental degradation and abstract, immaterial problems about art in general. Atmosphere is interesting in this regard because there is a historic overlap between “atmosphere” as an Earth system and in the sense of a place having a cheerful or gloomy atmosphere. We might also think of moments in literature, such as the story of the singer in Novalis’s Heinrich von Ofterdingen (1802), who escapes pirates by singing a song that literally causes the ship, the ocean, and the air itself to resonate in harmony. Or Anette von Droste-Hülshoff’s poetry, which thematises air pressure as a metaphor, but in so doing draws on what in her time was a novel insight, that the atmosphere does in fact literally press down on our bodies.

How would you describe Ashoka’s role in your book-writing journey? How do you see it contributing to your ongoing/upcoming research projects?

I am grateful to my colleagues and students at Ashoka University, without whom Ecology and German Realism, as well as my ongoing work, would not be what it became. Presenting the literature in translation to students in India has helped me to think about the authors from a more global perspective. The intellectual curiosity and openness of the students motivate me to pursue this work, both in the classroom and on the page.

Study at Ashoka