Empowering Lives and Building Connections: Stories from Assam’s Changemakers

Ananya Rao shares her field trip experience where she explored sustainable farming, education initiatives, and ethical reflections

Who are they, and what do they do?

Farm2Food (F2F) is an NGO working on sustainable farming and livelihood diversification in Assam. They are active in three districts of Assam: Jorhat, Dibrugarh, and Golaghat. They have been working in this region for ten years. Theory of Change Their entry point into the landscape is schools. Beginning work with children, they then scale their interventions to the parents of the children, then the village where the school is, and through this, they impact its ecology. They work with government schools to set up nutrition gardens and teach children organic farming methods. Through this, they reach out to their parents and promote similar organic farming practices with them. Once they have a good relationship with the parents, they begin working with village-level institutions such as SHGs and FPOs. They do not scale up higher than this.

What is it?

F2F sets up kitchen gardens in government schools, growing vegetables and greens. The children carry out the whole process. They learn how to prepare the land, make fencing, set up the garden, prepare organic fertilisers and pesticides, and grow local vegetables. The local KVK provides all the supplies they need for the entire process. The children sell the vegetables to the Midday Meal programme. They also sell the organic fertilisers and pesticides they prepare to farmers in the village. The money they earn goes to bank accounts that F2F has opened in each of their names.

Classroom Learning

F2F staff also organises science classes for students at the school. In addition to teaching sustainable farming methods, they teach other science topics in their syllabus, using engaging and innovative techniques. For this, they have developed one workbook on their own and multiple creative games and toolkits in collaboration with Ashoka (Bangalore) and Swiss Re. These games and toolkits are also provided to local teachers for them to use. In addition to teaching science, they also use these materials to teach soft skills such as leadership and entrepreneurship. The nutrition gardens are also used as ‘laboratories’ to demonstrate the concepts and theories the children learn in their textbooks.

A Solar Sakhi’s work

Solar Sakhis build torches, emergency lights, and fans. People in the village purchase them, as power cuts are frequent. Torches are for Rs. 500, while emergency lights are for Rs. 1500. Each Solar Sakhi tells F2F about the required supplies, and F2F orders the bulk from Barefoot College. Barefoot College supplies worth Rs. 10,000 for each Solar Sakhi for free. After Rs. 10,000, Solar Sakhi can buy new supplies from the profit she makes selling and repairing appliances. There are four Solar Sakhis in the Jorhat district. Anita, a Solar Sakhi in Jorhat, has diversified her livelihood through the following income sources – she grows paddy, rears chicken, ducks, goats, and silkworms, stitches clothes and sells them, and earns by building and repairing solar appliances.

Beej-daan

F2F also runs a Beej-daan programme in the villages to preserve local ecological knowledge. They ask children to collect indigenous seeds from every village household. Since it is local children asking, parents only give native seeds, not hybrid ones. In the process, the children ask each family to tell them about that seed—its cultivation, how it has changed over the years, etc. They then compile and record this information with the help of teachers and F2F staff.

Ayang Trust

Ayang Trust is an NGO working in Majuli island in education, livelihood, and health. The indigenous communities on Majuli island are highly vulnerable to flooding, as a majority of the island gets submerged under the Brahmaputra river every year. Ayang (meaning ‘love’ in Mising!) works on augmenting traditional livelihoods and providing good quality education to empower younger generations on the island.

Lekope

Lekope is a livelihood intervention programme set up by Ayang Trust. It works with women from the Mising community in Majuli. Lekope works with around 200 women to create handloom textiles and bamboo products. Traditionally, almost every home in Majuli has a loom, and weaving is a part of traditional livelihood practices on the island. Lekope uses traditional motifs and weaving practices to create sarees, cushion covers, shirts, and more—all sold on the island or online.

Hummingbird School

The Hummingbird School is a model school located in the heart of the island so that children do not have to travel for hours to reach school. It is set up on Majuli island to provide good quality education almost free of cost. The school was constructed from scratch entirely by the community. People from 13 villages came together to build it and to create a vision for what they wanted for their children. Every parent is involved in the school in some way – they each give one or two days every month to help out with cooking, farming, or any other service in school. The buildings are designed to protect against the recurring floods on the island. Like the rest of the island, the structures are built from bamboo and elevated by stilts. The school has laboratories, a library, and a philosophy of teaching what is within the textbooks and traditional practices such as farming and weaving.

Women!

Most of my work has been in very male-dominated universes. Whether it is farmer collectives, government offices, or forest rights committees—I have often been the only woman. I have always noticed the tremendous shift in energy that occurs when even one woman enters the space—it is kinder, lighter, and more accepting. Laughter enters the room. Given this, it was a remarkable experience to spend an afternoon with the women of Lekope. They were helpful, passionate, energetic, and open. They taught us so much while giving us a comforting space to just be for a while.

Homes

A habit I have picked up from my parents is photographing houses wherever I go. Homes across the country and the world—have incredible stories to tell. Majuli was no different. The houses of Majuli were invaluable windows into so many facets of the island and its people—environment, livelihoods, customs, and change. Most homes are built from indigenous species of bamboo. They are built on stilts to protect against flooding—a constant threat to the island. Fishing nets, looms, the season’s harvest, and all the necessary sources of subsistence and identity—are all part of the home itself.

Performance

I was very uncomfortable with the performances the children in F2F’s schools put up for us when we visited. It was not the field visit I was accustomed to or enjoyed. I thought it stemmed from unequal power hierarchies, where the school administrators told the children who had no say in the matter to put up a show for a group of visitors who were not contributing anything in return. However, I was also slowly made aware that the children who performed wanted to do so and were very excited about being able to share their talents with new people. It helped me shift my preconceptions slightly, as I realised that while power hierarchies exist, individual agency still does exist within them.

The ethics of a field visit

What do we contribute to the landscape and people we visit during field immersion? What do they gain from hosting us? Is it fair for us to demand someone else’s time when they do not have the choice or power to say no to us? When a teacher takes half a day to show us around his school and answer our questions, his 30 students lose lessons for one day. Is that fair? In such a situation, is it ethical for us to ask questions that merely pique our curiosity? The answers to which we will not be used to bring about any meaningful change. I believe it is inevitable that in any such immersion, we, the outsiders, cannot contribute as much as we take away. However, given the questions I raised above, I also believe that one approach to making the visit slightly more ethical is to rethink how such immersions take place—perhaps, to shadow members of an organisation rather than take tours from them. To ask questions, whose answers can we leverage to bring about meaningful change? To ask those we are visiting what we can contribute. These are still half-formed reflections They are just starting points towards a possible solution to my current dilemmas.

The concept of community

I would like to question the use of the word ‘community’ in my vocabulary and in others. It is an oft-thrown-around word in the development sector without considering that ‘community’ is never one homogenous entity. It is always, without fail, an amalgamation of different social, cultural, and political strands. In Jorhat, the ‘community’ was schoolchildren, paddy farmers, tea plantation workers, teachers, weavers, and herders—with one landscape containing all these people and often, even one person fulfilling many of these different roles. I would like to, in the future, pay more care to this diversity without constantly reducing the whole host of identities to one single entity.

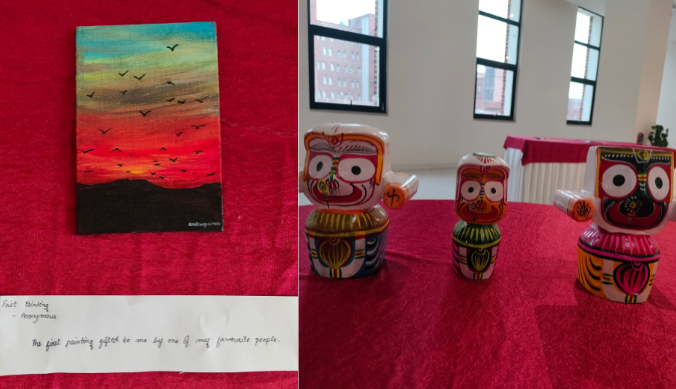

Friendship

In conclusion, I want to give a small shoutout to the wonderful friends I made with my co-fellows, facilitators, unexpected companions, and the people we met along the way! The conversations, the laughter and all the adventures made the entire journey a true joy.

(Ananya Rao is a Mother Teresa Fellow from the 2021 batch. She completed her Bachelor’s degree and Post-Graduate Diploma at Ashoka University in 2021 with an advanced major in Anthropology and minors in Environmental Studies and Political Science. She joined Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE) as a Research Assistant. Her areas of interest are forest rights, forest-based livelihoods, smallholder agriculture, the agrarian crisis, and governance of natural resources. She is pursuing a Master’s in Environmental Anthropology from Yale University)

Study at Ashoka