What We Experienced

Along with the historical remains what we experienced was a stunning landscape and a spectacular range of wildlife. The Bandhavgarh National Park has a jeep trail that is made for the visitors who are otherwise not allowed on foot or any other transport. Since we had been given permission to explore the forest on foot to conduct our survey we had the opportunity to go to those parts that only the people in charge of the forest and wildlife has access to.

‘Our’ Serpent Eagle

During our summer field visit in the months of March-April 2022 we would encounter a very stoic Serpent Eagle waiting by the structural remain at Siddhbaba looking around for food almost everyday. This serpent eagle became our lucky charm given the large amount of data we collected during that visit!

‘Varaha’ and deer families

During our rounds around the park we would come across families of wild boars and deer grazing and grunting away in all shapes and sizes. We would look forward to seeing them and have taken more photographs of them than our cameras could hold. The spotted deer and the occasional sambar were a pleasant sight to the eyes every time and the wild boars in their large numbers would just add on to our personal joke of finding a modern day “Varaha” presence in the park.

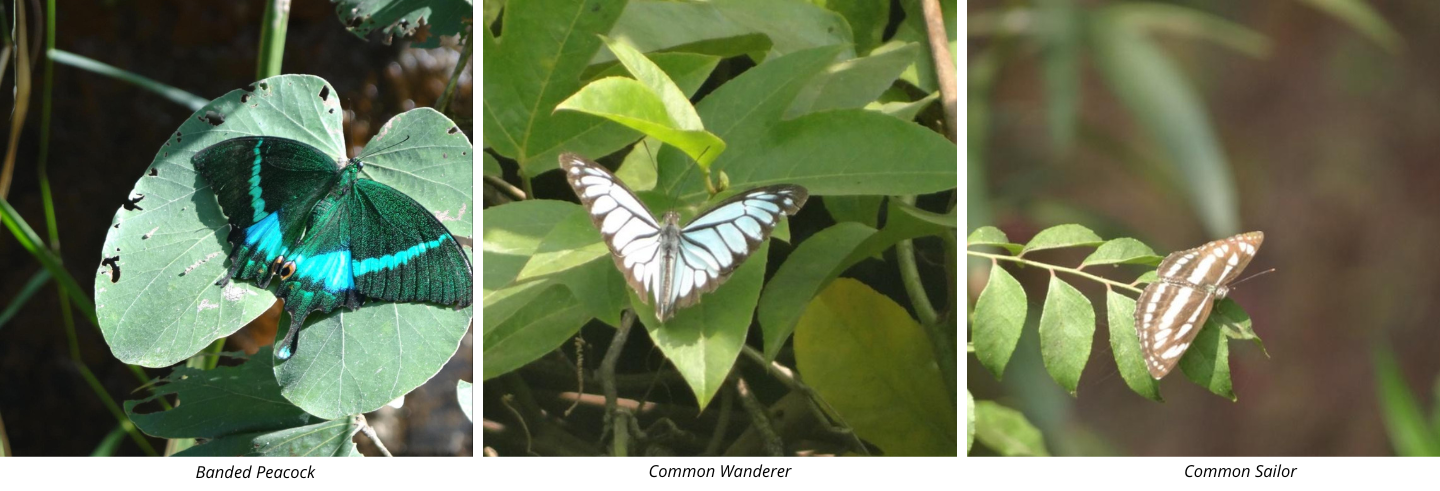

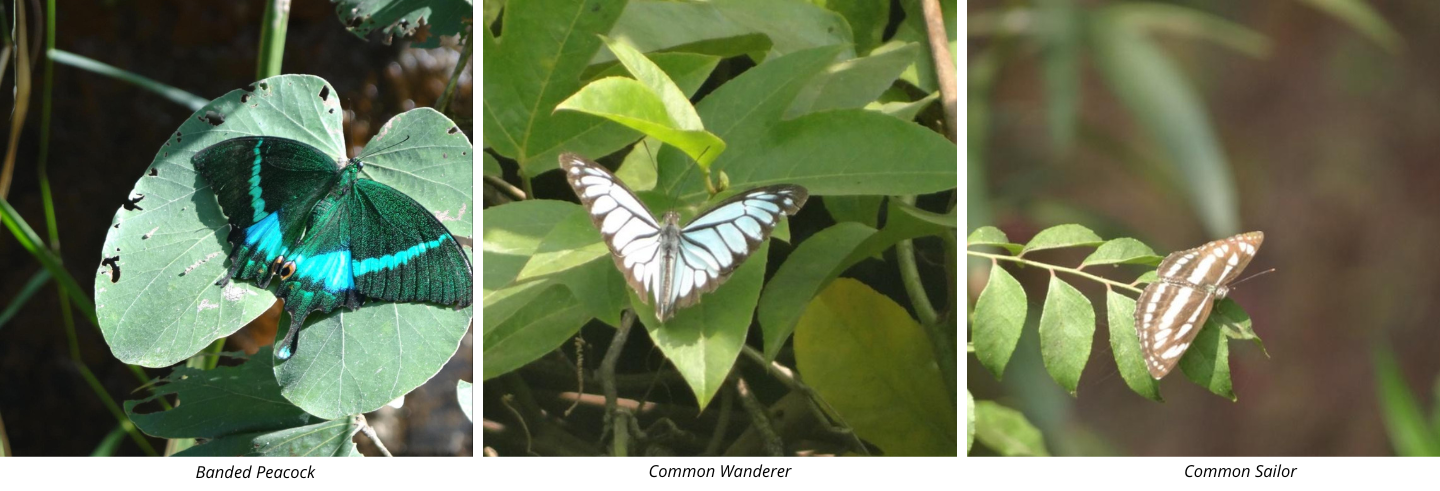

Butterflies and Birds

The very first day of our winter visit was marked by the sighting of a beautiful Banded Peacock Butterfly (left). During our stay in Bandhavgarh we saw a great many variety of butterflies such as the Common Wanderer, Common Crow, Common Gull, Common Emigrant, Lemon Pansy, Chocolate Pansy, Plain Tiger, Danaid Eggfly and the Baronet.

We also saw a range of birds such as the Serpent Eagle, Crested Hawk Eagle, the Lesser Adjutant Stork, Malabar Hornbill, Grey Hornbill, Egyptian vulture, Fishing Owl, Grey Wagtails, Common Bee-eaters along with several Coucals and Jungle Babblers.

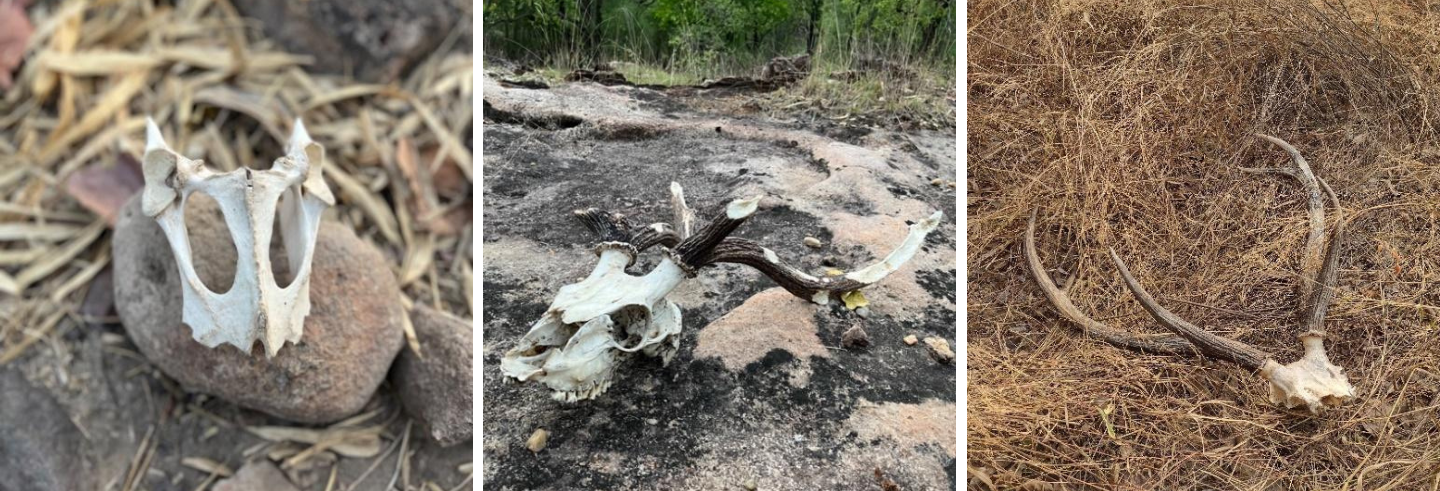

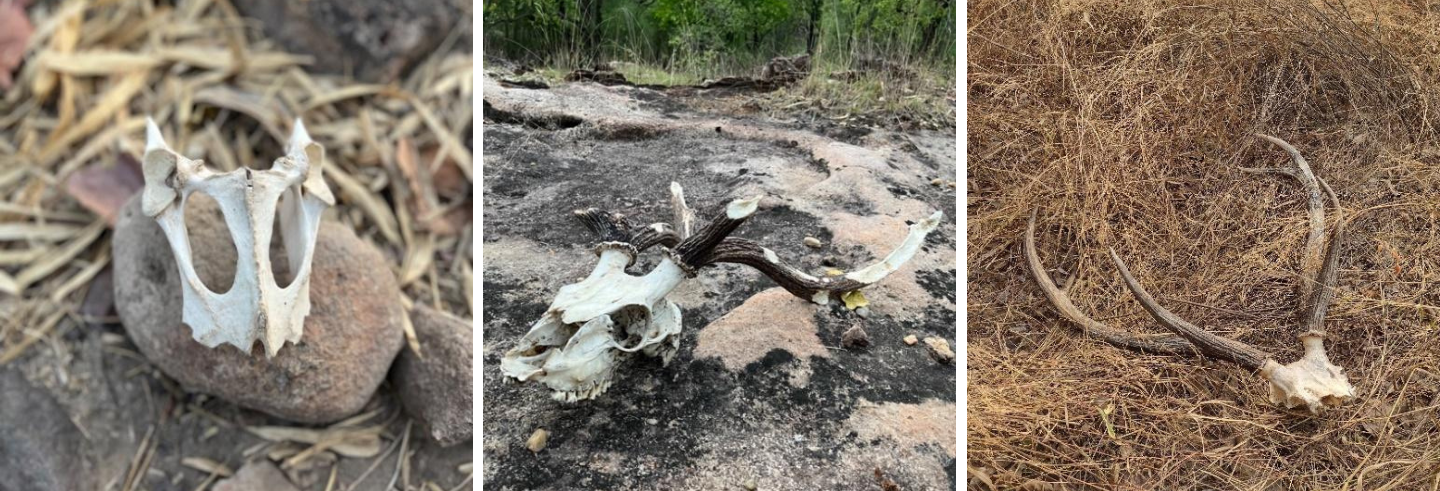

Skull-ridden path

One of the more exciting part of our walks in the forest was finding skulls and bone remains of animals that were either eaten by predators or had died naturally. We had found skulls of spotted deer, sambar and even of a freshly-eaten langur. Along with these we also found broken antlers and tusks of wild boar in the cave shelters. These added a dash of goosebumps to our already excited nerves!

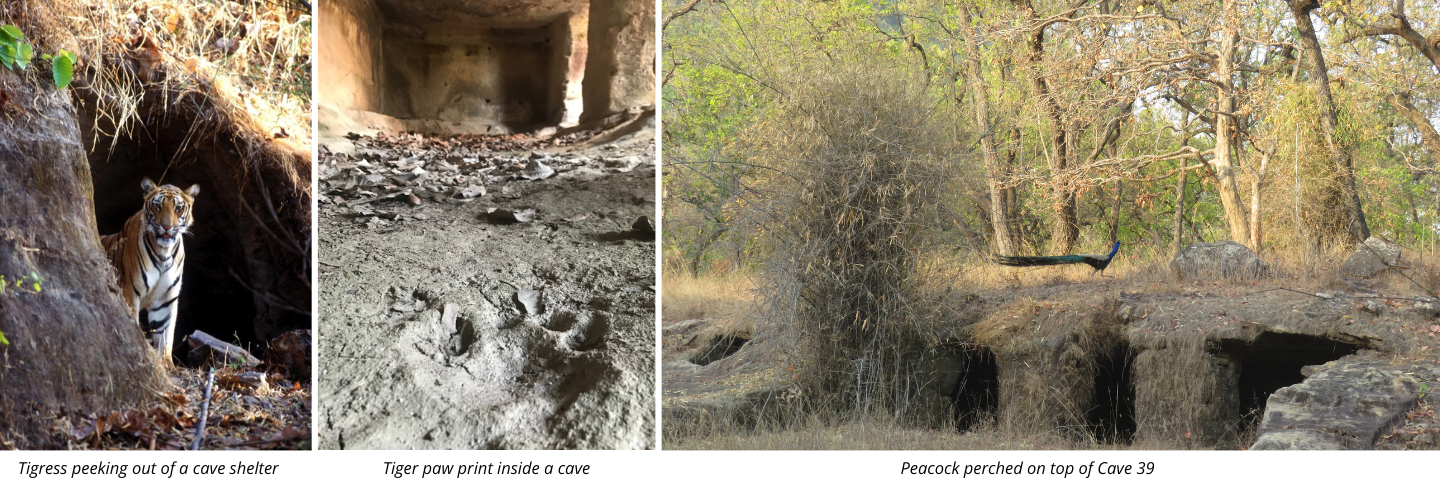

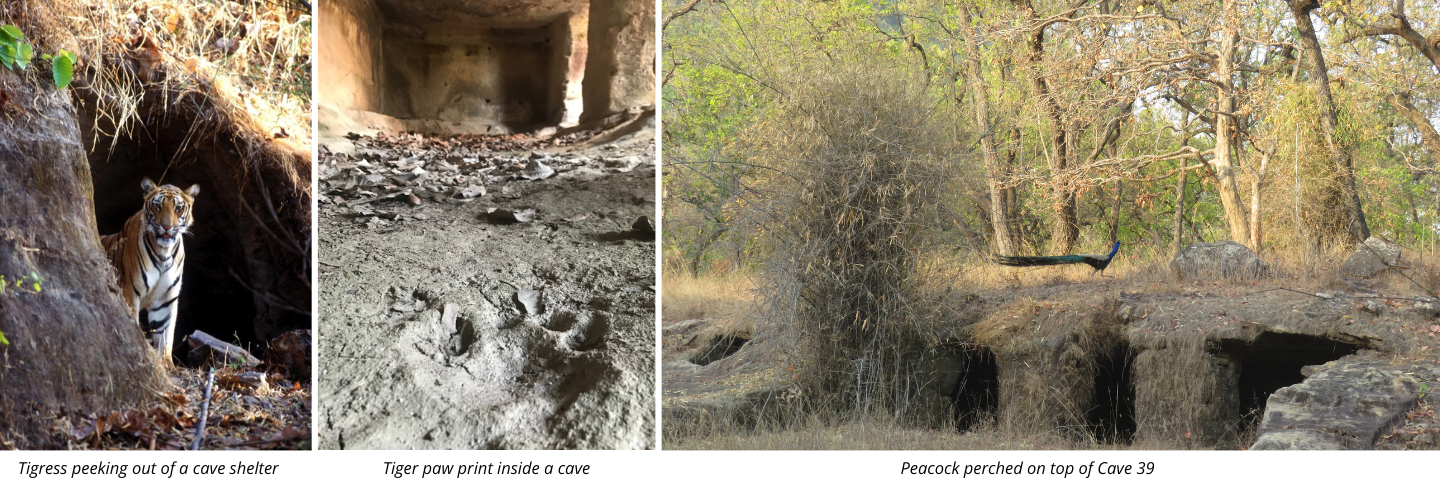

Caves and its present occupants

Ancient cave shelters were still very much in use! In many caves that we visited we would find proof of habitation. These occupants would leave bones and teeth and porcupine quills to leave us a clue about their identity. Even though we were not lucky (or unlucky!) enough to meet them in person during our visits, Mr. Tiwari has given us some incredible photographs that he had taken earlier from the back of elephants.

Leopard sighting

Leopards are generally elusive creatures as the likes of Jim Corbett and Kenneth Anderson would tell us, so when we had the experience of seeing a leopard cub in April 2022 we simply couldn’t believe our luck! This leopard stayed and even posed for a while we couldn’t take our eyes and cameras off of it.

Graced by the VIP

Most people visit the Bandhavgarh National Park to see the striped big-cats and they usually are successful. One day, we were taking a detour to check if there were elephants around and if we would be able to get off the jeep to do our work. Suddenly, our driver Santosh, slowed the jeep and asked us to look to our left. There she was, casually sitting on a rock. Bachhewali, as the forest guards fondly called her, gently stretched after seeing us before crossing the road and disappearing into the forest.

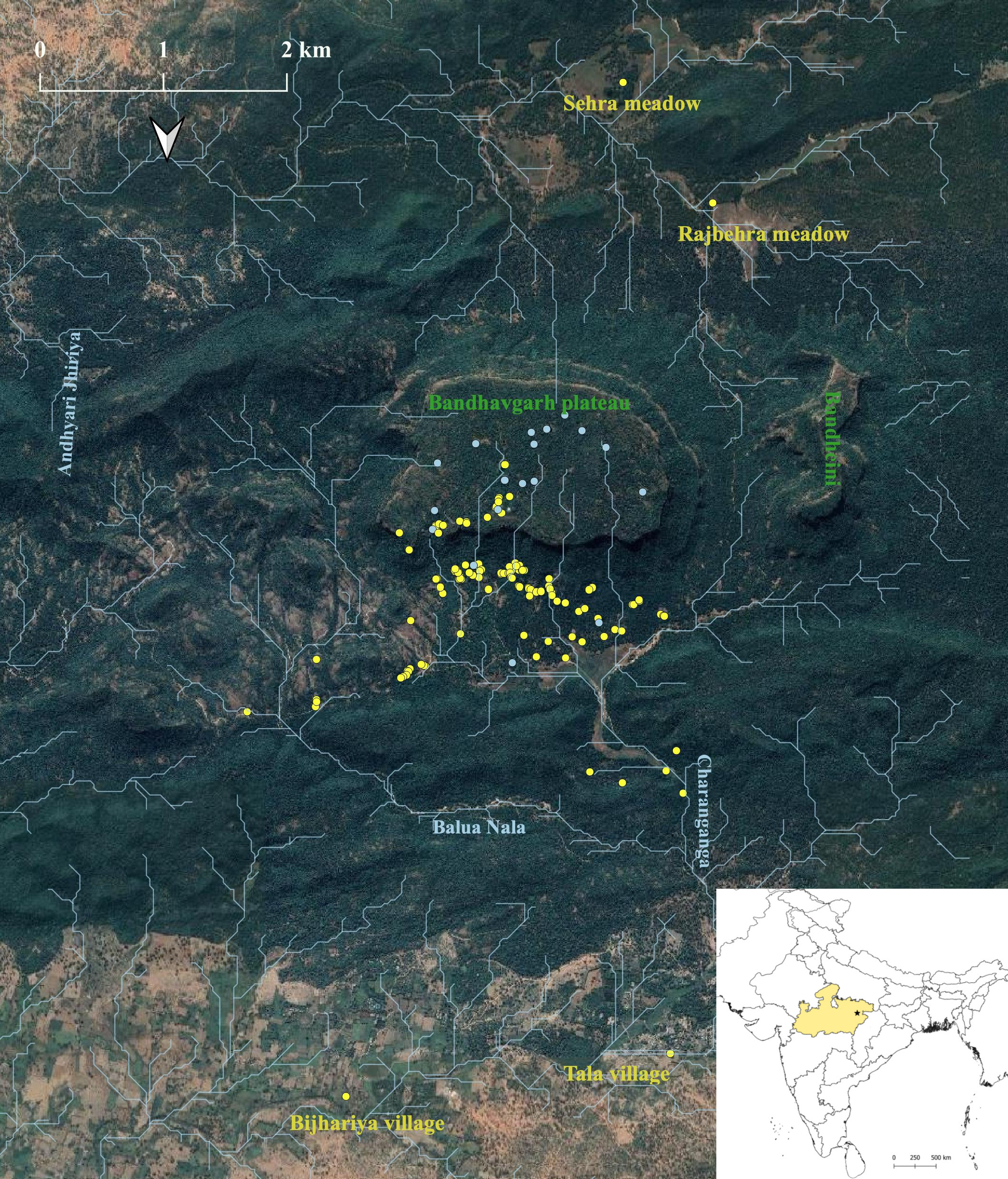

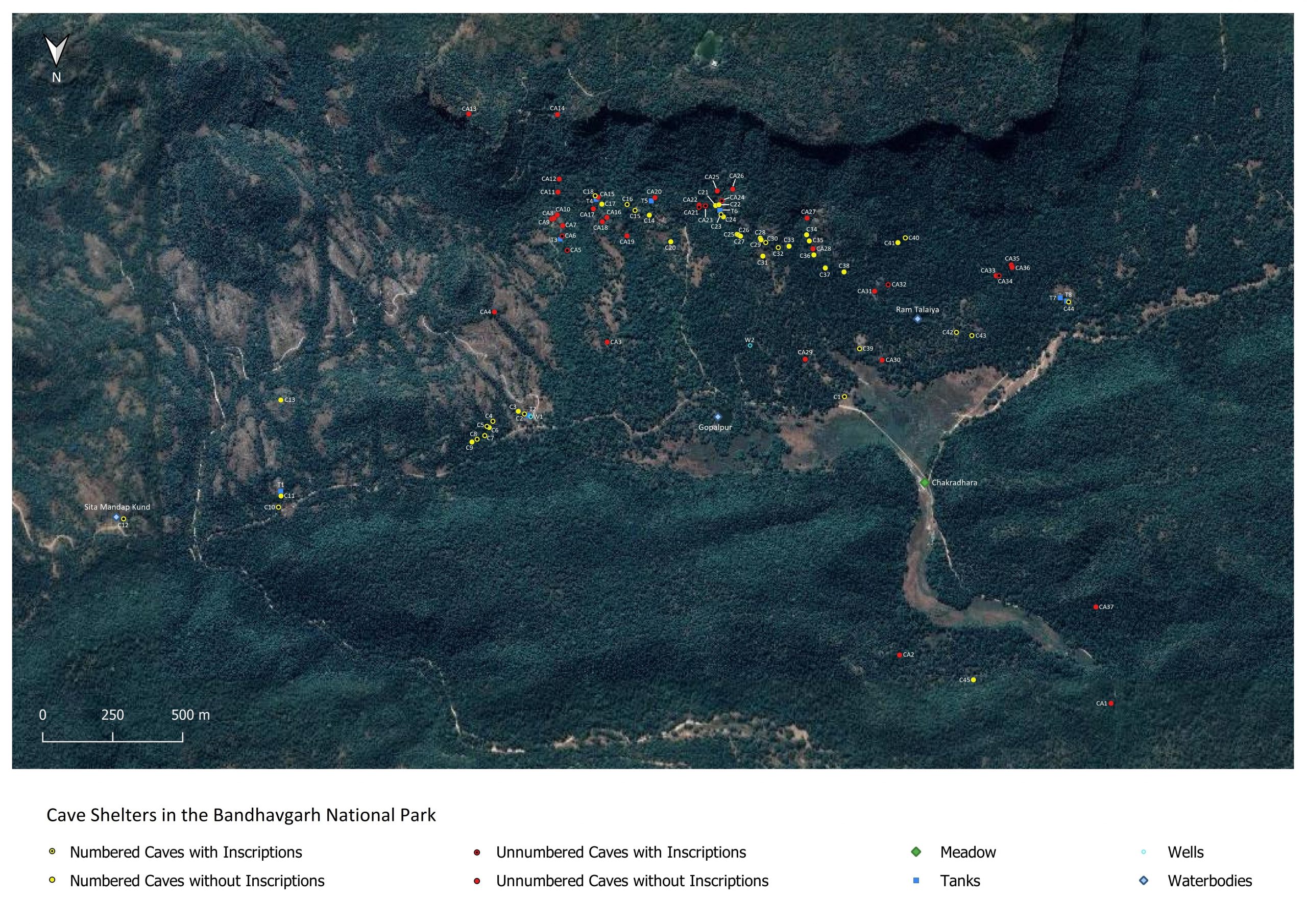

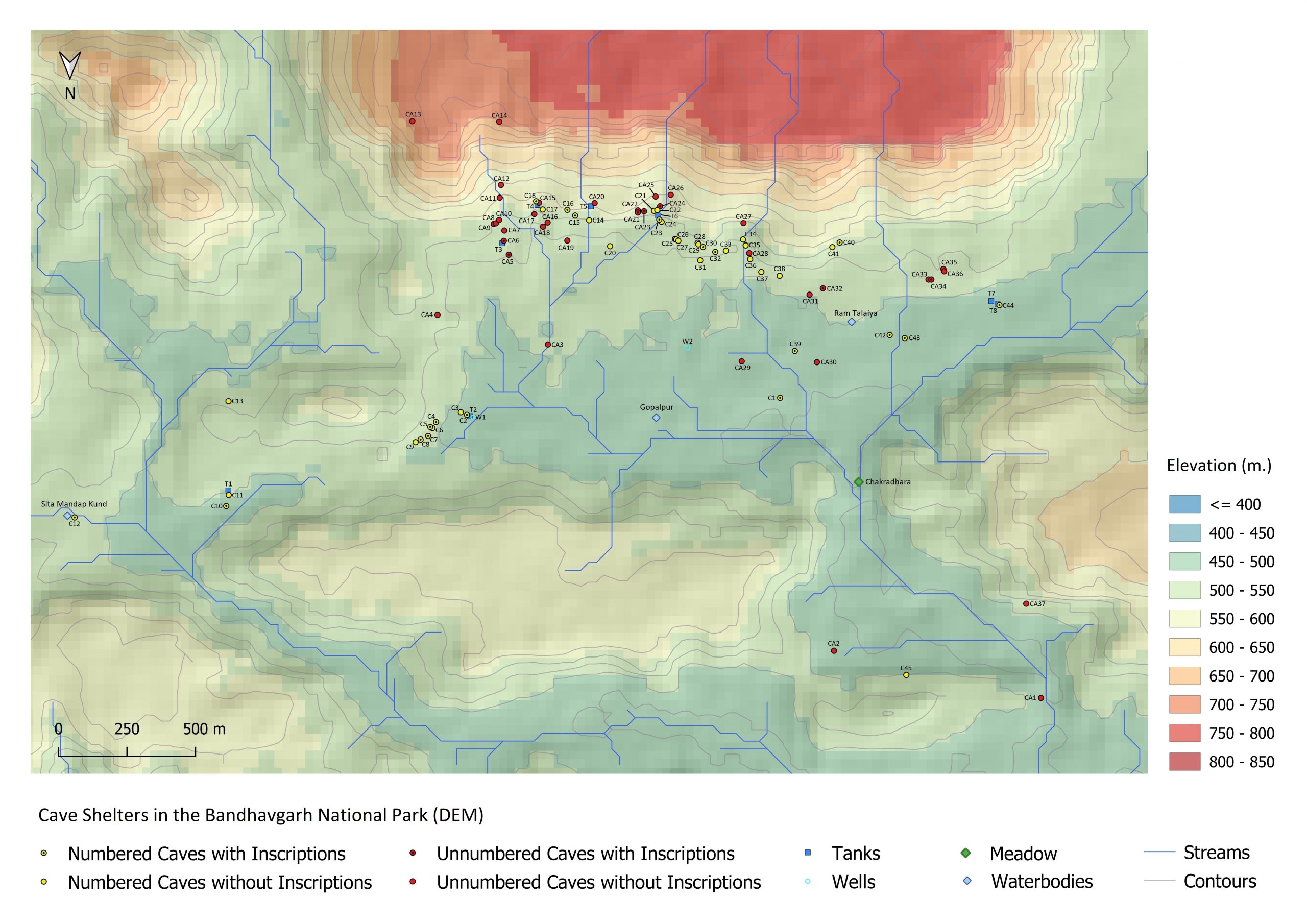

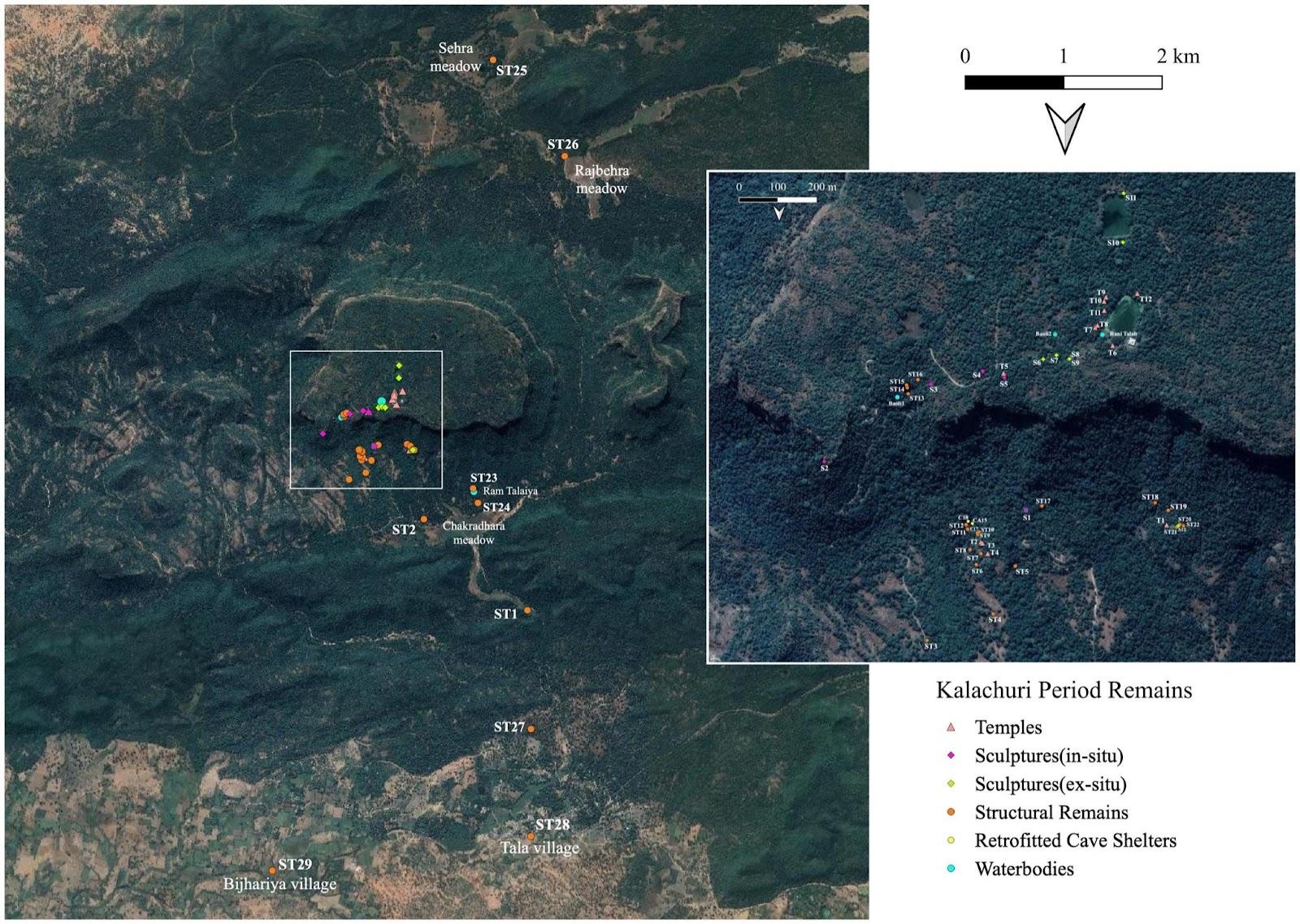

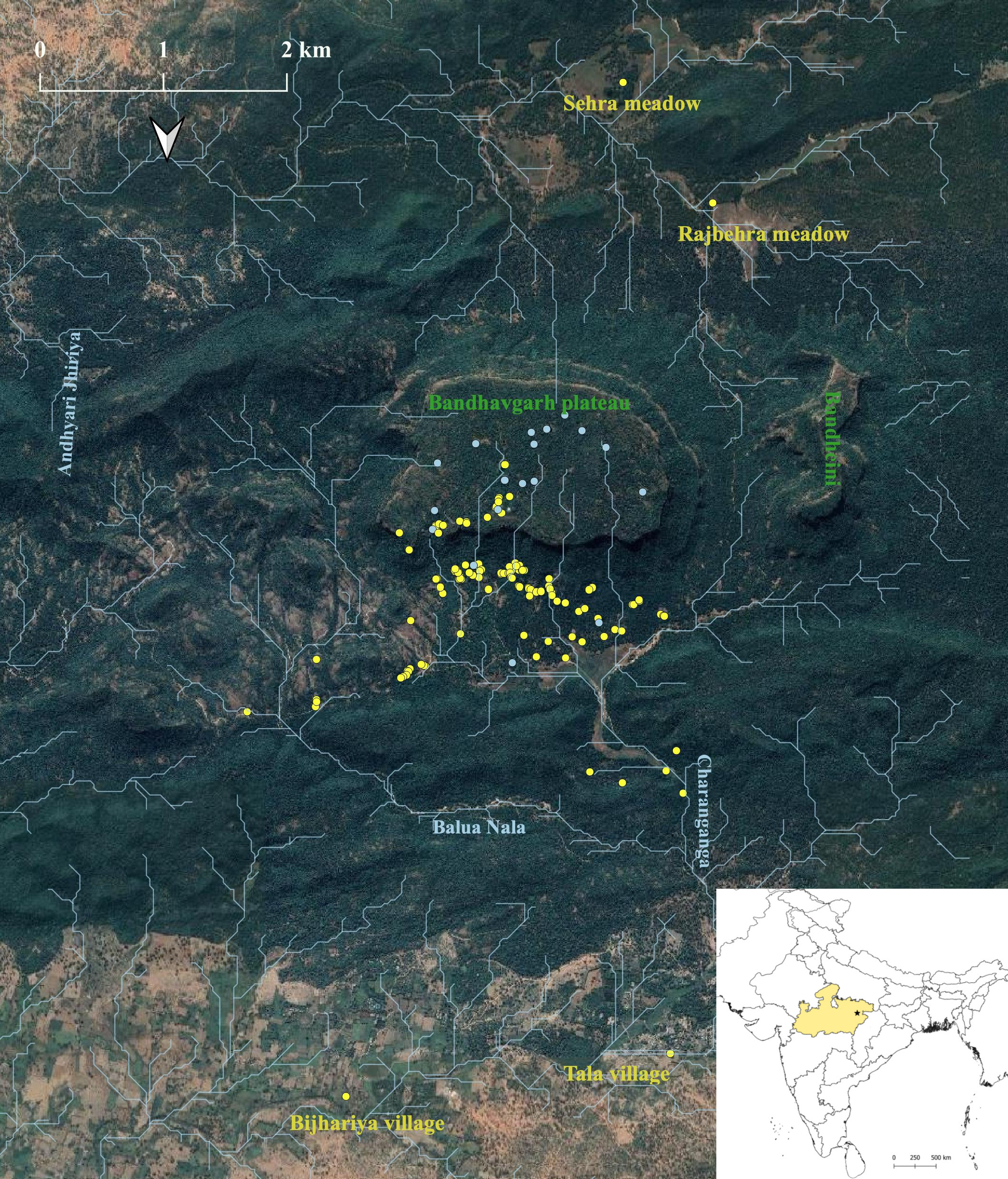

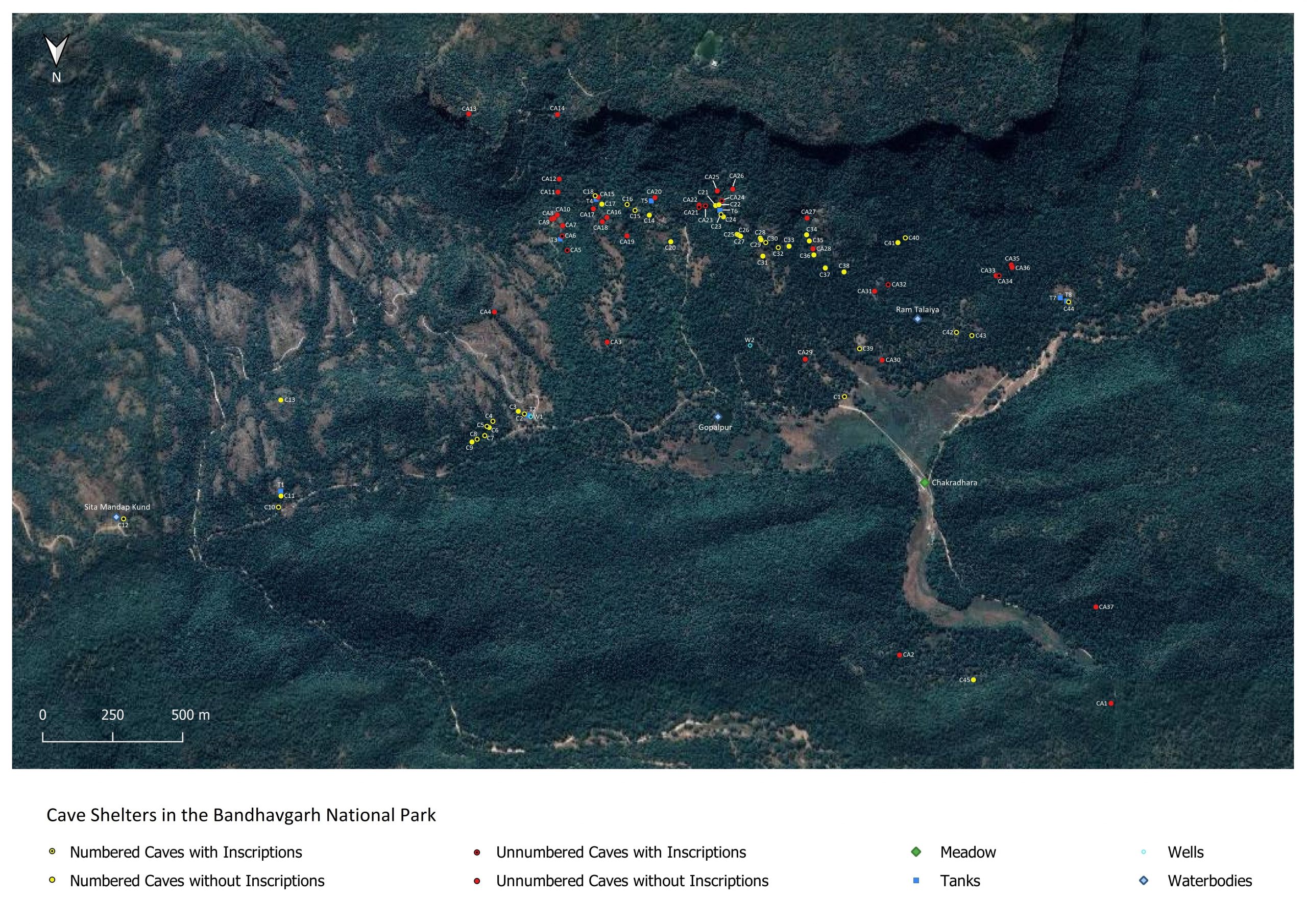

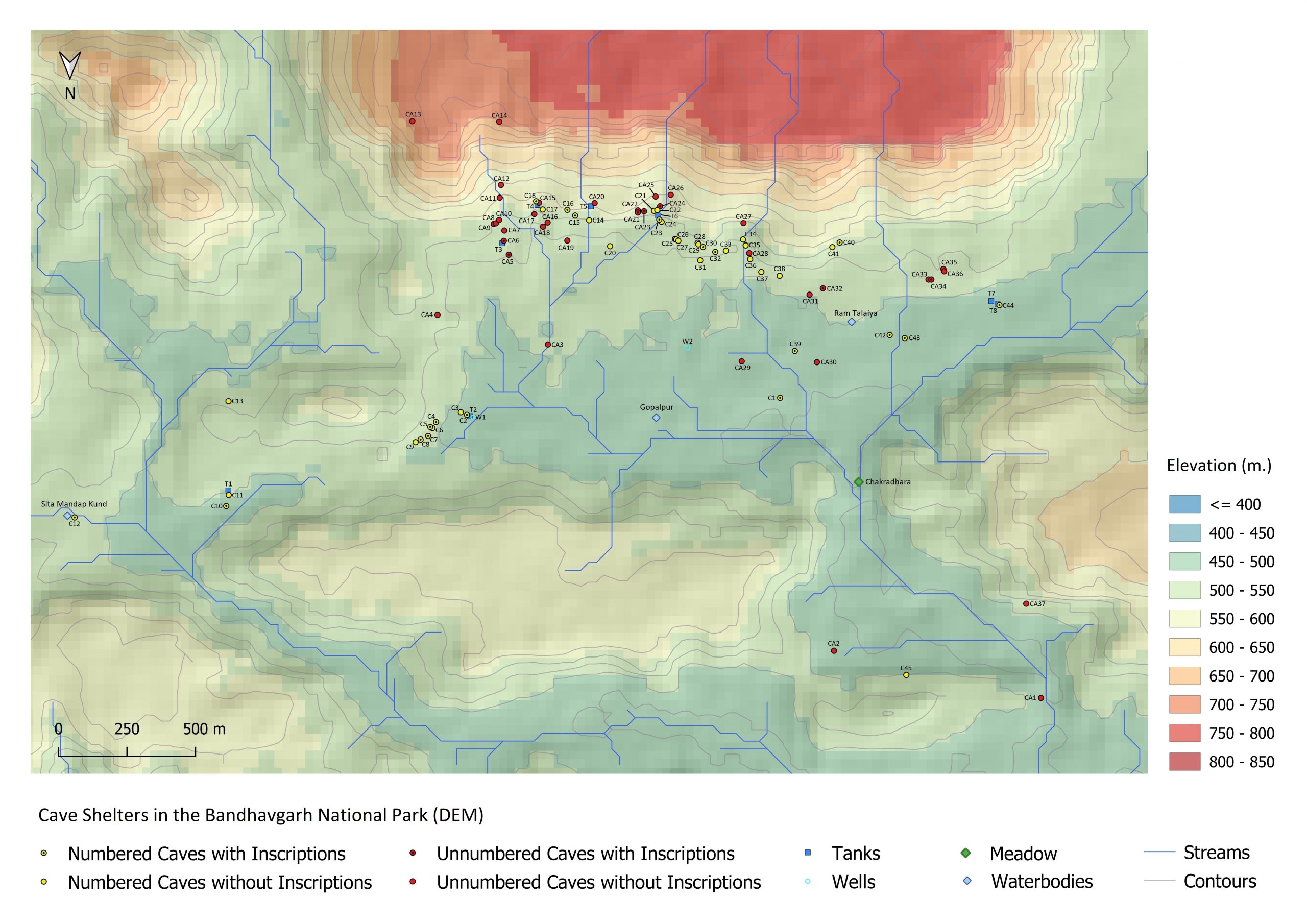

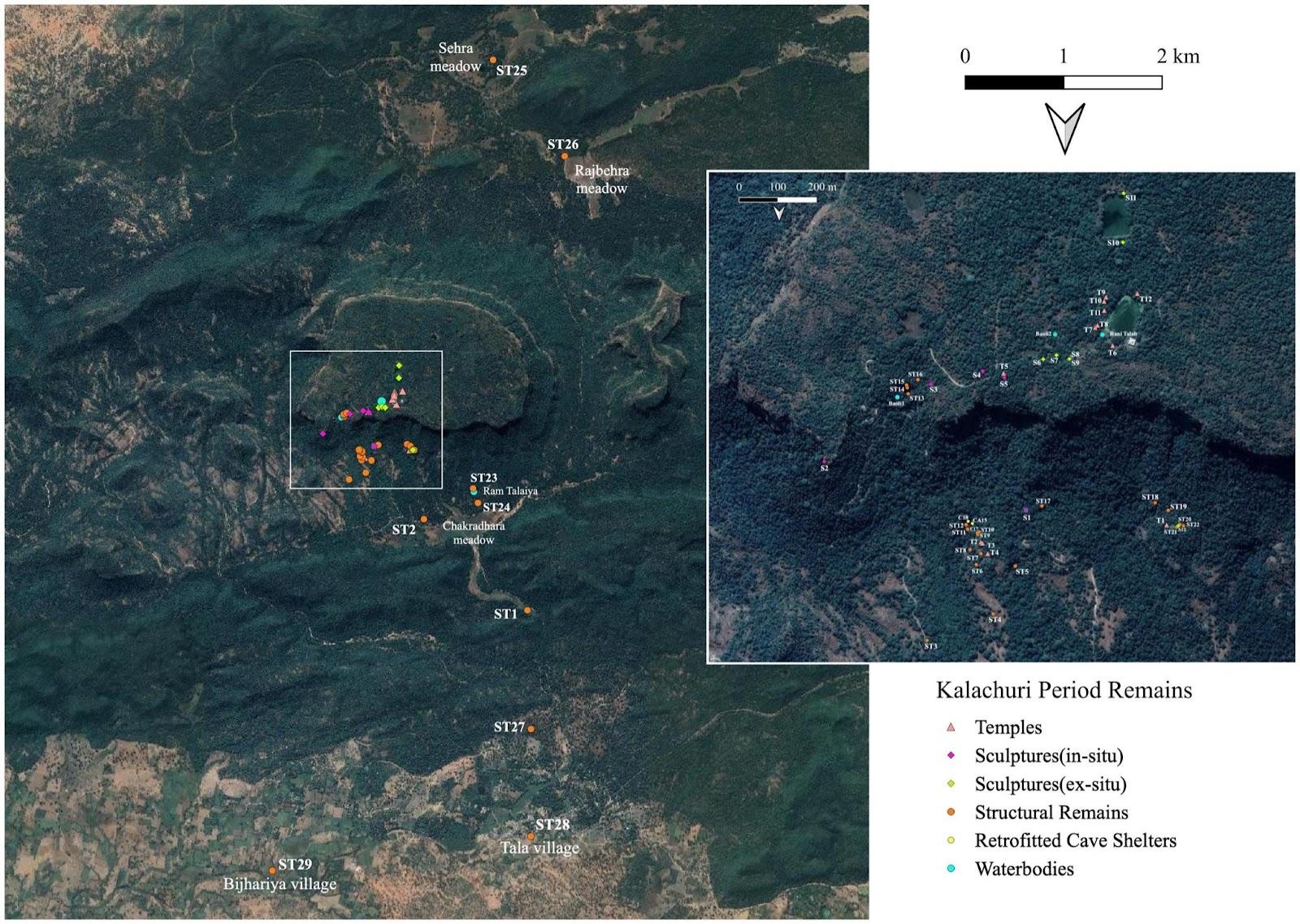

Maps Showing the Spatial Distribution of Archaeological Remains

Below are the maps we have made that shows the distribution and concentration of sites and remains in and around the Bandhavgarh National Park. These are created on Google Earth and on QGIS software. These maps give an idea of the entire study area including the nearby villages (fig 1), the spatial distribution of cave shelters to the north of the plateau (fig 2), a DEM or Digital Elevation Map showing the height and contours of the cave locations (fig 3), Kalachuri remains (fig 4 and 5), Vaghela remains (fig 6) and waterbodies (fig 7).

Figure 1: Map showing study area

Figure 2: Cave shelters and their spatial distribution

Figure 3: Digital Elevation Model of cave shelters

Figure 4: Kalachuri Remains in the Bandhavgarh National Park and adjoining villages

Figure 5: Concentration of Kalachuri period remains on and below the Bandhavgarh hill

Fig 6: Vaghela remains on the Bandhavgarh hill

Figure 7: Waterbodies inside the Bandhavgarh National Park