How Borders Move: Prof. Swargajyoti Gohain on Borders in South Asia

In this article, Swargajyoti Gohain, Associate Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Ashoka University, discusses her recently published paper, "Moving Borders in South Asia." She emphasises that her publication is not an outcome of a single research project, but an accumulated reflection of years of teaching and researching borders, and the realisation that borders are hard to grasp if we fix them in space and time.

What are borders? Are they geographical lines on the map, supported by fenced wires and checkpoints, separating one nation from another? Or is there a broader meaning to them? Several social science researchers have studied this problem in an attempt to understand the complex nature of borders and the factors that shape them. In line with this, Swargajyoti Gohain, Associate Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Ashoka University, discusses her recently published paper, “Moving Borders in South Asia.“

Prof. Gohain has been offering an elective course on borders as part of the Sociology and Anthropology programme at Ashoka University. She observes that one of the common challenges students face is in understanding the distinction between borders, boundaries, and frontiers. She notes that this confusion is not uncommon. If we review the available social science literature on borders, boundaries, and frontiers, we see numerous articles and books dedicated to explaining, analysing, and illustrating the differences or similarities between these terms and their definitions. This shows that many have realised and sought to overcome the conceptual conundrum known as the border.

Prof. Gohain highlights the role of modern cinema, particularly the war film genre, in popularising a particular notion of borders. These films have visually shaped the understanding of borders as the place where the nation ends, or where two nations confront and sometimes fight each other over territorial disputes. We are led too often to think of the border as that place out there, where we send our brave soldiers to keep vigilant watch. In everyday use, we interchangeably use “borders,” “frontiers,” and “boundaries.” Try as one might, it is hard to shake off these common-sense assumptions.

To address these conventional notions and limited ways of thinking, Prof Gohain advocates for the urgent need to adopt a broader understanding of borders. She poses the following key questions: Is the border something that exists out there, separate from our daily life? Is the border fixed in time once international treaties have demarcated it? Is the border merely a geographical concept, or can it also encompass other aspects?

In her recently published article ‘Moving Borders in South Asia’, Prof Gohain underlines how the border is a complicated beast by focusing on different empirical situations. The border moves in time, through space, is transported by bodies, is expressed in mental maps, and is transgressed both physically and figuratively.

To illustrate this complexity, she explores case studies from various contexts across South Asia.

One such case is the India-China border, the focus of the author’s anthropological work. In 1962, Chinese soldiers occupied for two months what was then Kameng, the western division of what is now the state of Arunachal Pradesh, bordering Tibet. The McMahon Line boundary demarcated by British colonial rulers in 1914 shifted, although briefly, in this instance.

Another case is that of the Tibetans who followed in the footsteps of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama to come to India as exiles. They are often questioned about their citizenship status. Living in different Tibetan settlements, they may have left the geographical border far behind, but the border is resurrected every time they face such questions. Their bodies are the border. Such embodied borders are also found among many other populations in South Asia, where speech, dress, appearance, or name mark someone out as not belonging to the nation. The border moves from its actual location through their bodies.

The dynamic of moving borders is also reflected in how identity documents have become the stamp of legitimate belonging. Passports, visas, registration cards are integral to proving our identity and our right to belong in a particular nation. What happens when we do not own or misplace these documents? We cease to belong. At checkpoints, airports, or railway terminals located thousands of miles away from the actual border, the act of border crossing is replicated when we are asked for documents. The border moves from its actual location here.

Our imagination transcends borders. For people who are displaced from their homeland, or dispersed between different countries, the practical reality of the actual border does not prevent them from imagining and aspiring to an alternative reality. Imagined geographies are the shifting borders of the mind that remain a hopeful possibility.

Reflecting on the expansive scope of the subject, Professor Gohain notes, “My article ‘Moving Borders in South Asia’ is not an outcome of a single research project. It is the accumulated reflection of years of teaching and researching borders, and the realisation that borders are hard to grasp if we fix them in space and time. Movement is a useful medium to explain shifting and changing borders. This article is an invitation to approach borders through the lens of movement and would be useful for lay and specialist readers alike.”

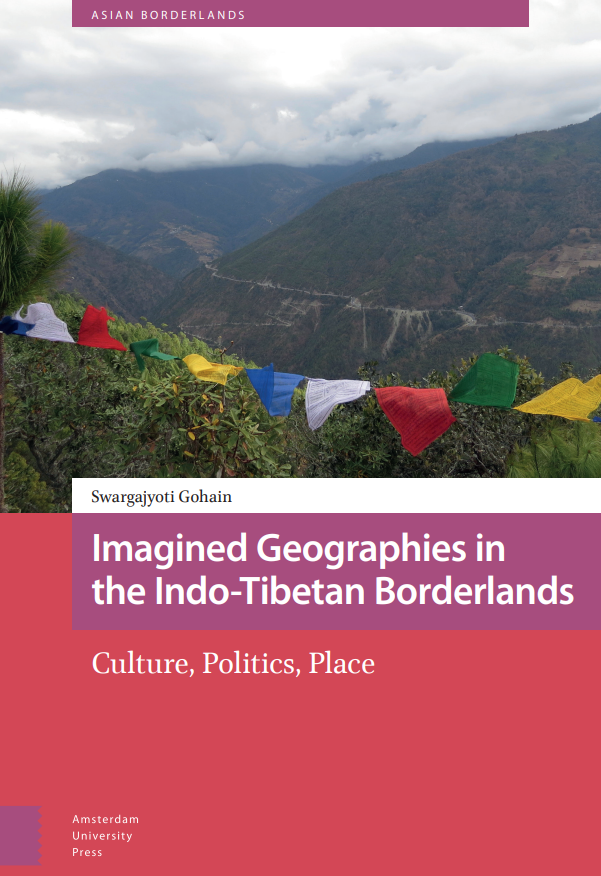

As a scholar of border studies, the author has conducted both field-based and archival studies of the subject. Her journey began nearly two decades ago, when, as a postgraduate student at the University of Delhi, she received a copy of The Bengal Borderland from a peer. Since then, she has been studying how cross-border histories and politics impact lives, livelihoods, and ecologies in the borderlands. In the context of the Indian Himalayan borderlands, her research emphasises that understanding Tibet, Bhutan, and Buddhism is essential to comprehend the events and developments in the region.

Continuing her research quest, the author hopes that more students in India from diverse disciplines such as history, anthropology, political science, and geography will take up the challenge of studying borders.

Study at Ashoka