“If Being Okay Means Divorce, Then I Choose Depression”: How do Indian Women Psychiatric Patients Navigate Normalcy and Illness?

In this article, Professor Annie Baxi, visiting Faculty of Psychology at Ashoka University, talks about her recently published research paper Negotiating Normalcy and Patienthood: A Dialectical View of Mental Illness Narratives Among Indian Women with Psychiatric Diagnoses. The study looks at women diagnosed with psychiatric conditions and how they make sense of their illness as well as construct their identity around that illness within the intersecting frameworks of normalcy and patienthood.

Women’s stories of distress reflect a complex interplay between societal ideals and personal suffering. Professor Annie Baxi’s research work tries to understand this complex relationship, noting that the same systems that constrain women also, interestingly, offer them a sense of belonging, self-worth and purpose. In this article, she talks about her recently published research paper on Mental Illness Narratives Among Indian Women with Psychiatric Diagnoses, published in the Journal of Constructivist Psychology, and shares her key observations.

Talking further about her recent research, Professor Baxi underlines that the traditional trends in psychiatric practices primarily focus on framing mental illness through either biological or psychological explanations. They do not pay enough attention to the moral and cultural factors that define both suffering and recovery for the patients. Whereas, in India, mental illness is inseparable from the social scripts that define what it means to be a “normal” woman, wife, or mother.

Her study explores how women, who are diagnosed with psychiatric conditions, build their identity around their illness and find meaning within the intersecting frameworks of normalcy and patienthood.

The study was conducted at a private mental health hospital in New Delhi, using a qualitative, constructivist approach with interviews and focus groups. The analysis focused on how women articulate their suffering through culturally resonant idioms, such as sacrifice and caregiving. In doing so, the study shifts attention from pathology to meaning, offering insight into how recovery is experienced as a process of moral negotiation, relational repair, and reclaiming dignity.

The findings revealed a dialectical tension between two competing identities:

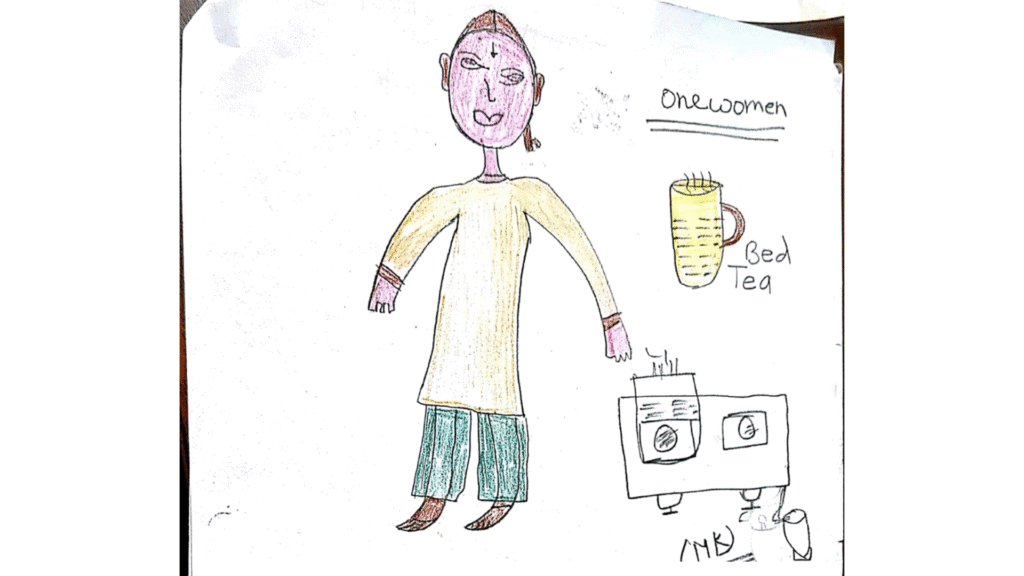

The normal woman — self-sacrificing, emotionally restrained, and devoted to family care.

The psychiatric patient — perceived as unstable, dependent, or morally suspect.

Their narratives reflected an ongoing negotiation between submission and resistance, as well as between patienthood and personhood. Professor Baxi, through her work, emphasises that understanding these dialectics is critical to their lived experiences, constructions of illnesses and related self-image.

Participants frequently referenced expectations surrounding sacrifice, caregiving, modesty, and domestic responsibility, positioning these as central to being a “good woman.” These ideals functioned not merely as abstract values but also as socially legible ways of speaking about self and suffering. Within the psychiatric institution, where women are often seen as symptomatic rather than situated subjects, reasserting normalcy became a form of resistance, a means to reclaim personhood against the clinical gaze.

Patienthood emerged as an ambivalent, affectively charged identity, shaped by institutional practices, cultural expectations, and personal histories. It disrupts social and domestic order but also enables women to reauthor their identities. Recovery, for many, was not separation from family roles but reintegrating into them with renewed meaning and self-awareness. Thus, rather than opposing forces, normalcy and patienthood coexist as dialectical spaces through which women continuously negotiate belonging, morality, and selfhood.

Based on these findings, the study encourages society to reconsider mental health as a condition profoundly influenced by social, moral, and cultural factors. For practitioners and policymakers, the findings underscore the importance of providing relational and culturally sensitive care that prioritises belonging, dignity, and moral worth alongside symptom relief.

The study suggests that hospitals and community programs must move beyond isolation to foster social reintegration through creative, domestic, and service-based activities that align with local values of connection and care.

Reflecting upon her research journey and observations in the given field, Professor Baxi says, “As a psychologist, academic, mental health practitioner, and most importantly as a woman, I have witnessed how women’s stories of distress reflect a complex interplay between societal ideals and personal suffering. Systems and structures that constrain women’s lives often also provide them with a sense of purpose, belonging, and moral worth.”

Professor Baxi’s research points out that for Indian women, recovery is not merely freedom from symptoms but a restoration of relational balance and social usefulness. Through her research, she reinforces the idea that a dialectical approach to therapy has the potential to bridge the gap between biomedical treatments and lived experiences. It reaffirms the desire for individual identity and the desire to be relationally functional. By engaging cultural narratives rather than dismissing them, practitioners can promote more inclusive and meaningful models of healing that affirm both vulnerability and wholeness.

At a broader level, the study contributes to emerging global dialogues in psychology that seek to decolonise mental health research by situating distress within its moral and cultural ecologies. It highlights how listening to patients’ stories, especially those of women in non-Western contexts, allows us to understand mental illness as a human effort to live meaningfully within, and sometimes despite, societal expectations.

Study at Ashoka