ShistoDx: Automating Diagnosis of Schistosomiasis

Vaibhav Shokeen, a fourth-year student at Ashoka University, chronicles his field visit to Nigeria and shares insights from his work on automating disease diagnosis.

I am a final year computer science and mathematics undergraduate student at Ashoka University, Sonipat. This blog post is about a project I’ve been working on since March 2024, which me and my teammates at the time named SchistoDx. It is an attempt to automate the diagnosis of a waterborne parasitic disease called Schistosmiasis by integrating a deep learning and computer vision based software solution with a special microscope called the planktoscope.

Meeting the mentor

During my internship at the lodha genius programme in 2023, I got the opportunity to be a teaching assistant for a 2 day workshop organised by Professor Manu Prakash. He’s an innovator whose ted talks I used to watch back when I was in class 9 and think how cool the frugal devices he built are, very simple toy like instruments costing no more than a dollar or two which could perform tasks that’d usually require equipments worth a few thousand dollars.

At the end of his workshop he recommended that I take his Frugal Science class in 2024 if I was interested in his work and wanted to delve a bit deeper. This is a course which anyone across the globe could attend for free and learn about some of the problems that affect us on a global scale and have the potential to be solved with some frugal innovation. Two of the major themes in the course were around global health and environment. It was an exciting time when I’d be looking forward to a class at 11 pm in the night. Frugal Science is a project based class, we needed to work in teams and try to develop a solution to address any problem of our choosing to pass the course. A learning from this class that I always try to keep with myself is to have an “and, not but” mindset. Manu emphasizes a lot on building on other’s ideas instead of jumping on to find a problem with them.

Discovering the problem

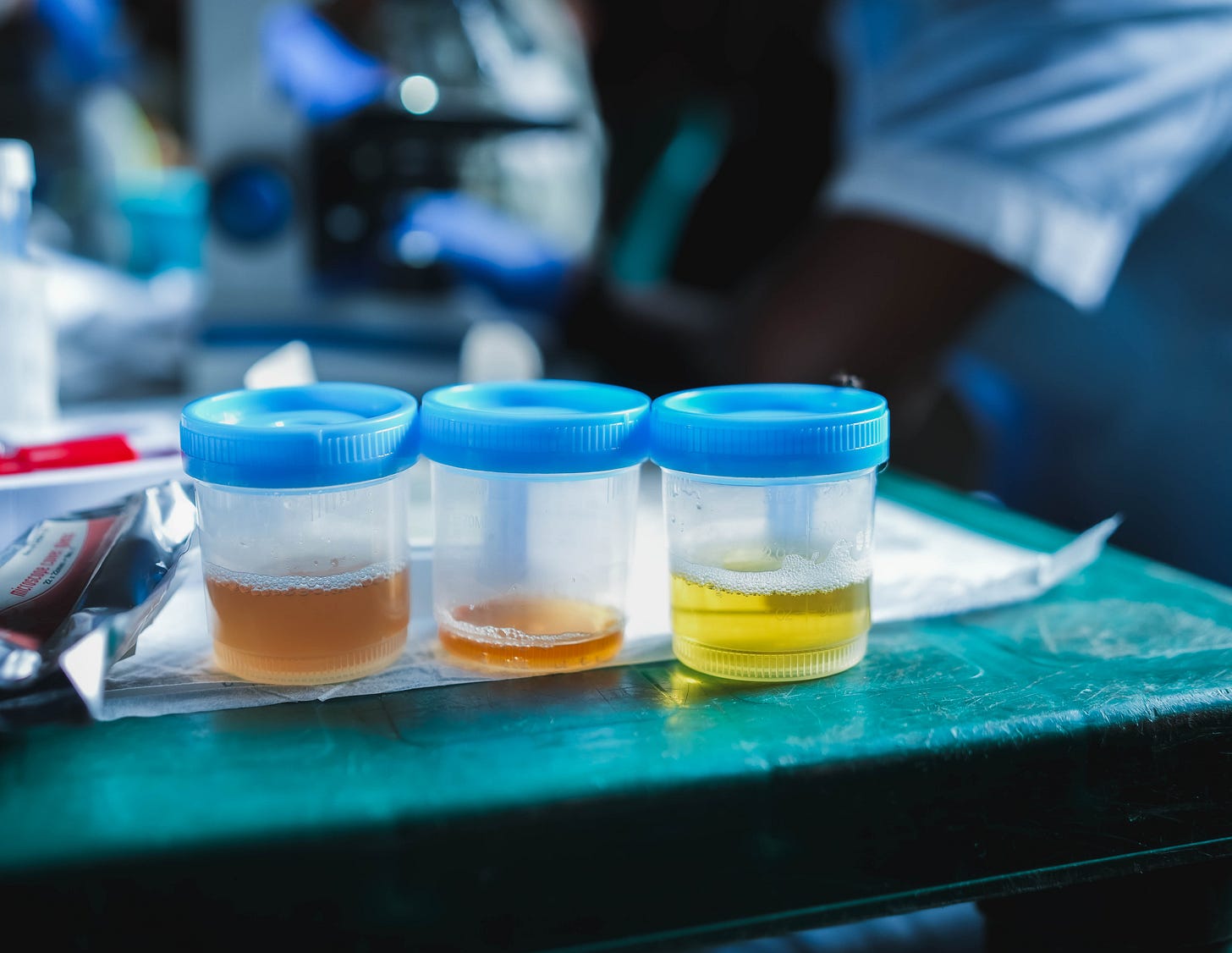

I heard of Schistosomiasis in of these classes where professor explained its a Neglected Tropical Disease(NTD) which affects over 200 million people living in rural communities that lack access to clean freshwater. It is caused by a parasite which enters the body when a person comes in contact with contaminated water, it then starts laying eggs in the body which can be detected in urine and faecal samples depending on which species of the worm it is. If the parasite has lived in the body long enough, which is often the case in the affected communities, the patient’s urine turns red because of damage to the urinary tract.

He recounted an anecdote which stuck deep with me. A father takes his son to a local health worker, concerned that his son is not well the father says to the health worker: “Something is wrong with my son, he is not menstruating.” This shows how prevalent the disease is in some areas, leading the locals to believe it is normal to have red colored urine. At that time I was in my second year of undergraduate with not much to do other than coursework so I thought if there’s even a slight contribution I could make towards eradicating the disease then why not give it a shot?

The problem with currently popular methods of diagnosis is their labour intensity and low sensitivity. Some of the communities which are affected would have access to a doctor only once in a year or two, and the pathologist would have to diagnose an entire village alone by looking at the samples under a microscope themselves. We made a team to try and automate this process which would take the burden off of the on-field pathologists and also increase the sensitivity of the test while trying to keep the cost under $2.

Developing the solution

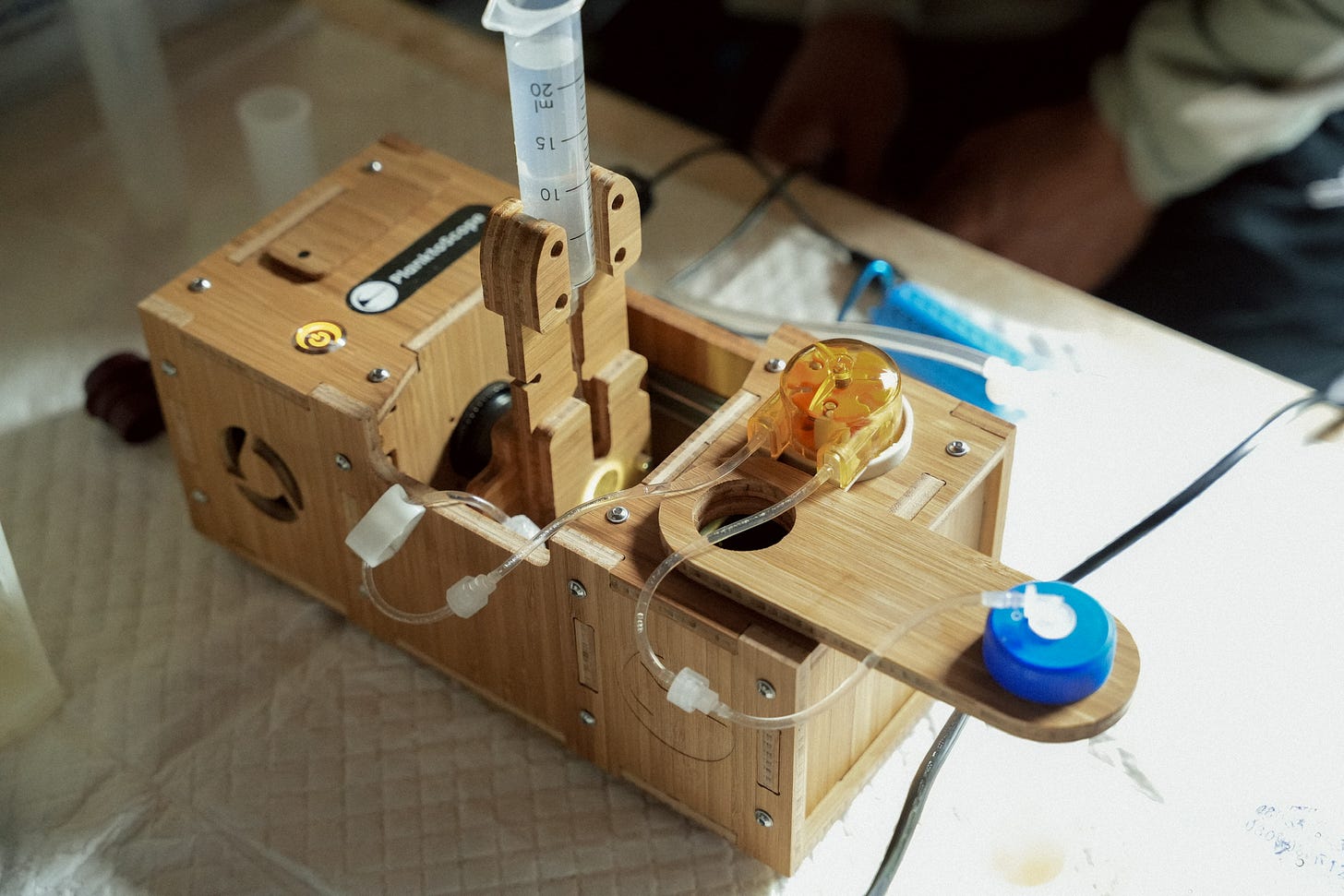

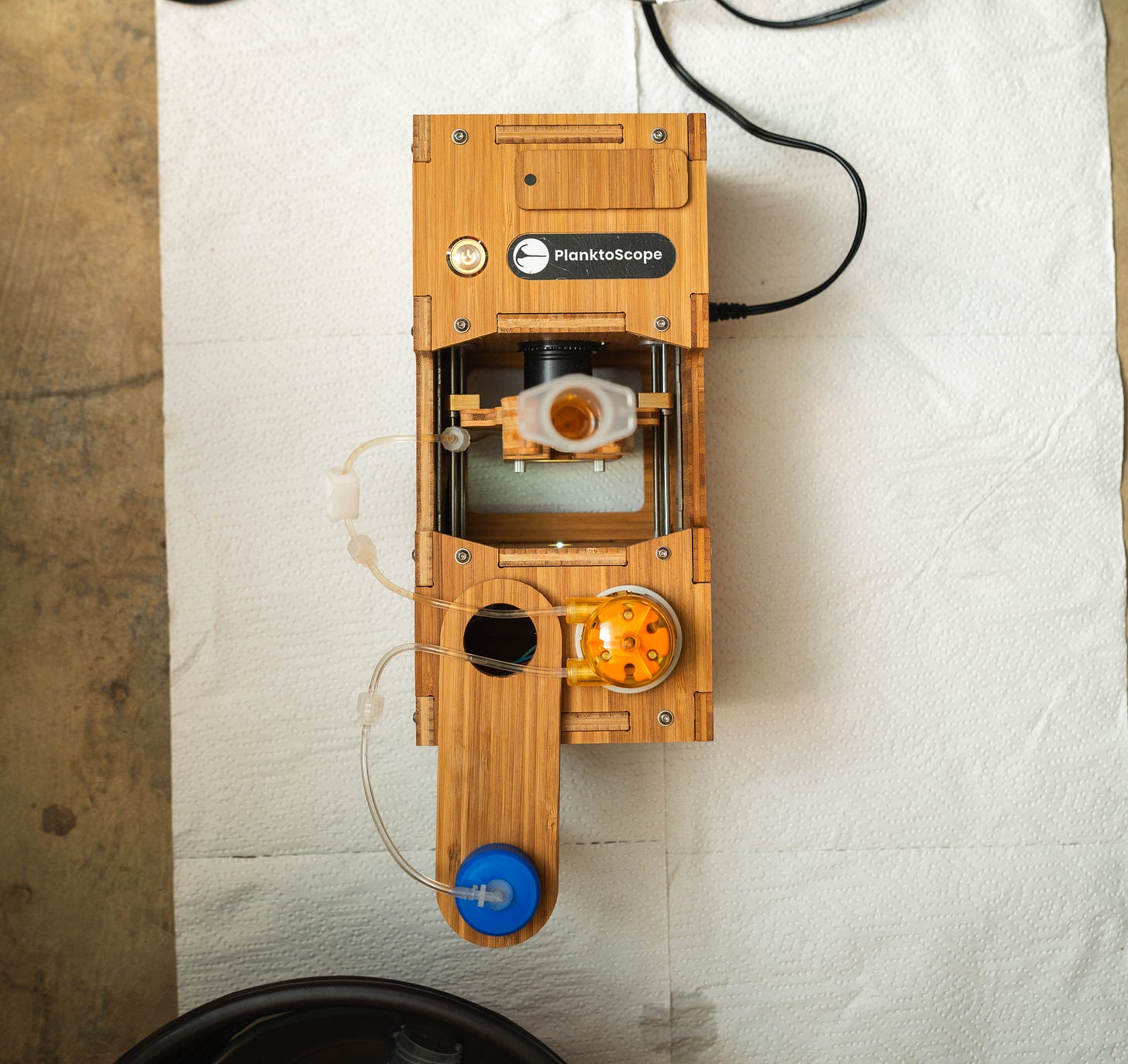

I was part of a team of 4, comprising 2 PhDs in bioengineering and 1 MSc in bioengineering. All 3 of them were studying at Stanford. A planktoscope is a flow-through microscope which can take images of an high volume of fluid sample at high magnification.

Our idea was to click images of the sample on the planktoscope and then we’ll pass those images as an input to our ML model which would predict whether an egg was found in any of the samples or not. The team at Stanford explored how to best image samples on the planktoscope and I, having a computer science background, explored what models would work best for our use case.

Two strong candidates for our model were EcoTaxa which specialises in identifying sea planktons and YOLO, an open-sourced object detection and segmentation model. After experiment with the model provided by EcoTaxa and the model we developed using YOLO, we chose to go ahead with YOLO as it provided much more accurate and faster results. The deliverable at the end of our course was a model which showed promising results with our data, however, there were some obvious aspects we needed to work on. One, for example, was that we artifically created the training data in the lab using chemically preserved Schiso eggs instead of working with real samples which we knew would be look very different from the ones we created. We were able to show that this line of diagnosis has a lot of potential once implemented on field after further research.

Applying for the grant

After the end of the class, I got convinced that this project was very practical and scalable. So I really wanted it to not stop at just a slide deck and be implemented in the field. I was very fortunate in here since Manu was able to guide us to the right resources and we applied for a $10,000 grant at the Experiment Foundation to be able to travel to affected areas and collect data to fine tune our model and also understand the problem at the grassroot level. Right after my end semester exams ended in May, 2024 I received an email congratulating us for receiving the entire amount of the grant!

At this point the other members of the team were no longer able to continue further with the project due to other important commitments. I now became a sole researcher from Sonipat with no background in healthcare or medicine who was trying to automate diagnosis of a disease which doesn’t even affect India. After a few months of infrequent communication, I was finally able to meet Manu in November, 2024 where we briefly discussed how to proceed with the project.

It was quite challenging to figure out a way with experiment.com to receive the funds in India due to several limitations with the international transfer of funds. I finally had access to the grant in December, 2024.

Planning the field visit

The first thing I needed was the planktoscope which was critical for my project, I was extremely fortunate in having the support of Fairscope when the instrument was slapped with a hefty custom duty in India. The field visit would not have been possible if I had to pay the entire duty amount myself and hence the kind folks from Fairscope helped me by pitching in. I was able to receive the instrument in Februrary, 2025 and it took me about a month to familiarize myself with operating it.

Now that we had sourced sufficient funds and the instrument, the natural next step was to plan a field visit. Manu now introduced me to a wonderful team that was planning to do a field study in Nigeria sometime in July, 2025. The team was planning to explore two new methods of diagnosing Schistosomiasis, one was a molecular based test and the other was using the foldscope, and compare the results with the current WHO Gold Standard for diagnosis of schistosomiasis. They were happy to add me in the crew so that I could collect data to train my model for detecting the parasite eggs.

It was so amazing that I met the team only once over a google meet in May, 2025 and we all just planned an entire trip to Nigeria over emails afterwards.

Trip to Nigeria!

After passing through an extraordinarily difficult visa application process, I successfully landed in Nigeria on 22 July, 2025. We stayed at the Conference Hotel, Abeokuta from where we’d travel to different communities(four in total), living around the Ogun reservoir, for eight days.

We’d get into a van around 7:45 am in the morning, pick up rest of our local crew members from around the city and drive for a few hours to reach our destination typically around 11 am. We’d then set up and start our testing which would go on till around 3 pm, at which point we’d start packing and leave by 4 pm at the latest. Then we would usually end up back at the hotel by 6 or 7 pm.

The days were extremely hectic but also energising at the same time, I had never before seen such overwhelming curiosity from an entire village about anything. Children and adults alike were very interested in interacting with us, learning about what we were doing, and also teach us more about their culture and language. I’m somewhat confident in my Yoruba (which my Nigerian friends do not approve of yet).

It was hard to operate with just one battery in the first few days since my laptop, the planktoscope, the compound microscope, and other devices also required power but we learnt to rationalize on the power eventually and each of us was able to carry out their part of the experiment. While the team diagnosed 410 people over the eight days, I was only able to image 14 samples. The imaging process was slow(about 90 minutes per sample) because I was focusing on collecting high quality images to train the model on. Once we have a sensitive model, it is easy to speed up the imaging process on the planktoscope. This will hopefully be tested in the next field visit!

This was my first time seeing the effects of the disease up close and interacting with the affected communities, it was an entirely different level of understand than reading a report or paper on the web. It made me all the more motivated to see this project through and being implemented at scale.

In conclusion, I have been associated with the project for a significant amount of time now and this 11 day field visit alone made all the time I spent worth it. I had never before interacted with such an enthusiastic and purpose driven group of people before. Living in the cities, it’s easy to assume that most of the world now has access to the internet and other technologies which we are used to seeing around but the reality in a lot of places is in stark contrast with this assumption. I’m now very motivated towards developing technologies and solutions which can possibly permeate into these parts of the world.

Study at Ashoka