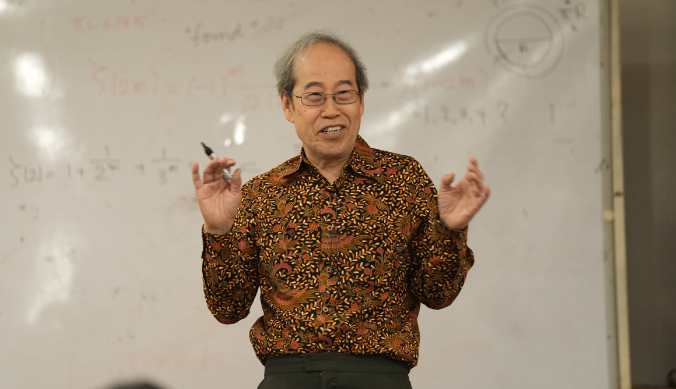

“Microscopes Aren’t Just Tools of Discovery, They are Windows Into the Unknown”: Dr Hari Shroff

Physicist, biologist, and microscopist Dr Hari Shroff speaks to Ashoka about building tools for science, the role of AI, and learning from young minds.

Dr Hari Shroff is a globally recognised leader in advanced optical imaging and microscopy. Currently a Senior Group Leader at the Janelia Research Campus (HHMI), he is best known for developing high-resolution, live-cell imaging tools that have transformed how scientists observe biological systems in real-time. After completing his Ph.D. in Biophysics at UC Berkeley, Shroff worked alongside Nobel Laureate Eric Betzig at Janelia, contributing to the development of super-resolution techniques such as PALM. He later led the Section on High‑Resolution Optical Imaging at the NIH, where he continued to push the boundaries of light microscopy. In this engaging conversation at Ashoka University – part of the Lodha Genius Programme’s Great Ideas Seminar series – Dr Shroff shares his journey from building his first instrument as a teenager to leading pioneering research, reflects on the power of interdisciplinary collaboration, and highlights the inspiring energy of India’s next generation of scientists.

You’ve worn many hats – physicist, computer scientist, biologist. How do you personally define your identity as a scientist? What do you call yourself?

Hari: In my work, I’m kind of uncomfortable with labels because our work spans a great number of things, as you’ve just said. You know, my bread and butter is sort of taking tools from physics and engineering and building tools to inform biologists about things that they can see. If I had to call myself something, I guess I would say I’m a microscopist. I like to build microscopes. And I’m passionate about applying them to image biology.

You’re based at the Janelia Research Campus – a name that sparks curiosity but doesn’t immediately reveal what the place is about. Could you tell us more about what Janelia is and what makes it unique as a research environment?

Hari: Janelia Research Campus is part of the larger Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), which is the second-largest nonprofit biomedical funder in the world after the Wellcome Trust. In the early 2000s, HHMI was thriving and primarily supported labs across the United States through grants. At the time, with its endowment performing well, the institute had a choice: either expand its funding to support twice as many university scientists or explore a new direction for impactful investment.

They chose the latter, establishing a dedicated research campus designed to foster a “biological Bell Labs” environment. The goal was to create a space where scientists could pursue ambitious biomedical questions that often fall outside the scope of conventional funding. What began as a rough idea sketched on a napkin eventually took shape in 2005–06. The building was completed in 2006, and I was among its first employees.

As for the name “Janelia”, it’s a unique one, and there’s a charming story behind it. The campus is located on several hundred acres in Virginia, about an hour outside Washington, D.C. The land was originally a historic farm, owned by a farmer who had two daughters named Jane and Cornelia. When the property was sold, one condition was that the name “Janelia” (a blend of Jane and Cornelia) be preserved. The campus was initially called the Janelia Farm Research Campus, though over time, the “Farm” was dropped.

Janelia brings together physicists, biologists, and computer scientists – all under one roof, collaborating closely. What does a typical day look like for you in such an interdisciplinary environment?

Hari: One of the most unique aspects of Janelia is that it was intentionally designed to bring biologists and tool builders together – a collaboration that doesn’t always come easily in traditional academic settings. Although the campus is relatively small, with fewer than a thousand people, everyone works in a single building. This setup fosters a high frequency of spontaneous interactions, what we like to call “collisional” exchanges – between physicists, biologists, and other scientists. My day typically involves a mix of activities: mentoring and supporting my team, pursuing our own research, brainstorming ideas with colleagues, and collaborating across labs. I also share access to my microscope to help others advance their work — it’s a very collaborative and dynamic environment.

Do you incorporate AI in your work, particularly in tracking brain development or analysing biological systems?

Hari: Yes, we do use AI to some extent. Microscopy often involves difficult trade-offs – for instance, to see finer details, you need to shine more light, which can damage the sample. Or if you want to capture images faster, you reduce the signal in each frame, lowering the signal-to-noise ratio. These physical limitations make things challenging. That’s where AI, particularly deep learning, becomes valuable. That said, a key caveat remains: AI is only as good as the data it’s trained on. Like arge language models, these tools can “hallucinate” when faced with unfamiliar inputs.

So while they’re powerful additions to our toolkit, they must be used with care and a clear understanding of their limitations.

You started incredibly early – I believe you built your first scientific instrument when you were just 16. That’s quite different from what most teenagers are doing at that age. What led you down that path?

Hari: I may have been a bit older, but yes, I built my first instrument around that time. I was fortunate to have an unconventional academic journey. I enrolled early in a special programme at the University of Washington that allowed students to skip high school and begin college. It was the right fit for me – traditional schooling wasn’t quite meeting my academic needs.

It was a lucky and formative experience. I had the freedom to try things, to turn theoretical concepts into something real. That early exposure to hands-on research – using what I’d just learned to explore something unknown – was probably what sparked my lasting fascination with academic science.

What stood out to you about Ashoka University?

Hari: On the academic side, I toured several labs and was genuinely impressed – the facilities and quality of research here are on par with top U.S. universities, and in some cases, even better funded. For example, your light microscopy facility, which is free to use, is extraordinary – even at Janelia, we have to allocate lab budgets to access similar equipment. On the student side, it’s been a joy engaging with such bright, motivated individuals. It’s inspiring to see young minds come together, network, and explore cutting-edge tools and ideas. Opportunities like this are rare, and my advice to anyone here would be: make the most of it.

What is the message that you would like to give to youngsters who would like to explore the micro world?

Hari: I think it’s a great time to be a microscopist, and the wonderful thing about exploring the micro world is that there’s plenty of room. So, you know, if you decide to go into science, if microscopy is a large part of your world tool, chances are very, very good. You will see something that nobody has ever seen before. So let that be, maybe, hopefully, an inspiration to you to use microscopes in your work.

Study at Ashoka