Sonipat – Sites and Sights

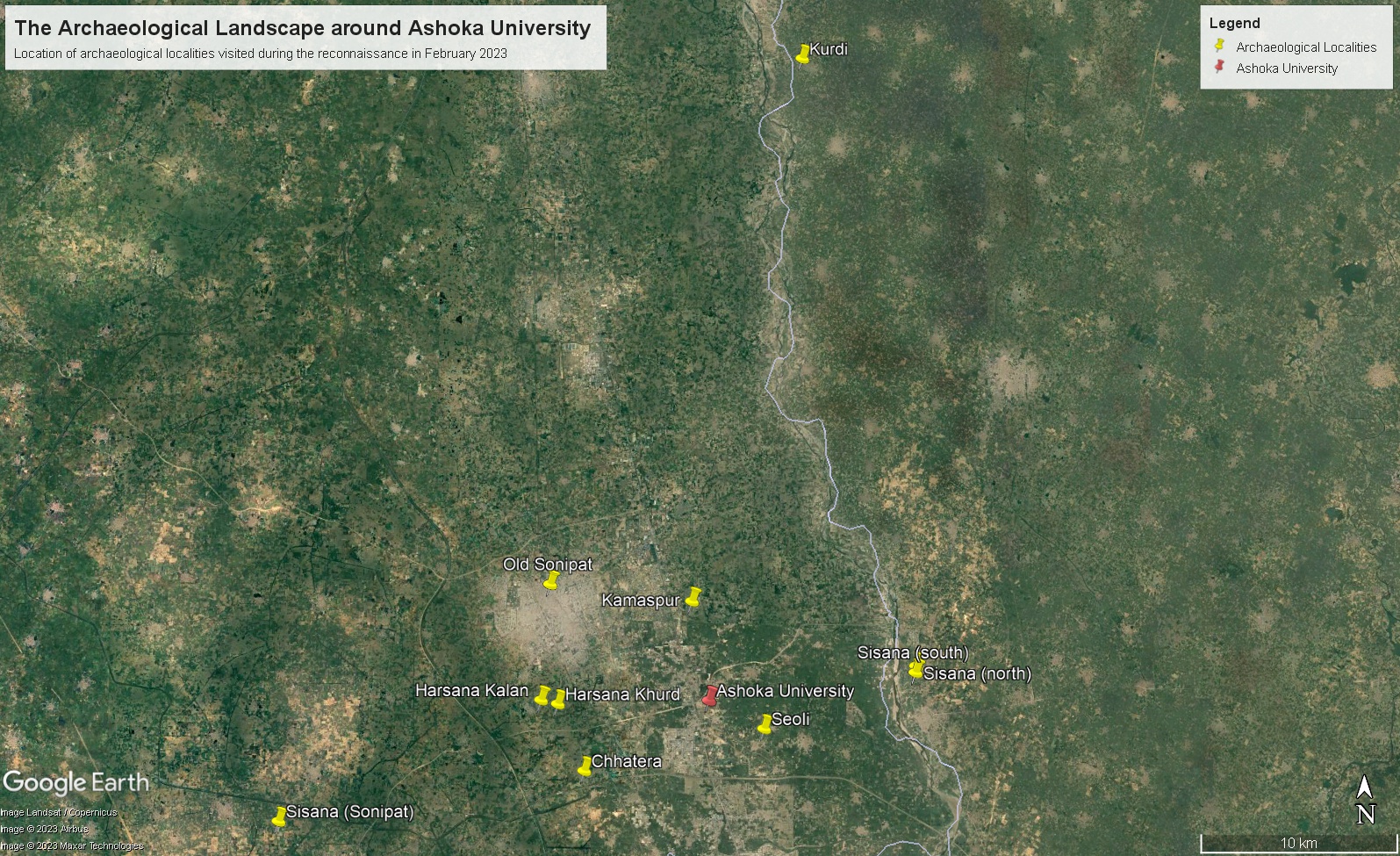

What is it about Sonipat and its surrounding areas that speaks of its history? And how does one sight the sites where this is inscribed? With the aim of exploring old places there, Ashoka University’s Centre for Interdisciplinary Archaeological Research commenced a survey in February 2023.1

The surveyed terrain ranges from sites in the floodplain (or ‘khadar’) of the Yamuna river to older alluvial tracts (or ‘bhangar’) in Sonipat district (Haryana) and Baghpat district (Uttar Pradesh) which lies on the eastern side of the river. What we encountered was a hodge podge of archaeological remains that are surviving cheek by jowl in the midst of modern villages and towns, fields and factories. There are ancient mounds which look like low and high hills standing above the flat plains. The ceramics lying on the surface and in eroded sections of such mounds are indicators of their antiquity. There are also pottery scatters in cultivated fields, and there are medieval relics ranging from Mughal ‘kos minars’ (distance markers) to wells. All of this – the archaeological sites and the monuments – gives a first-hand feel of being in the presence of a past going back to the second millennium BCE and continuing into the sixteenth century and later.

Which is the closest archaeological site to Ashoka University?

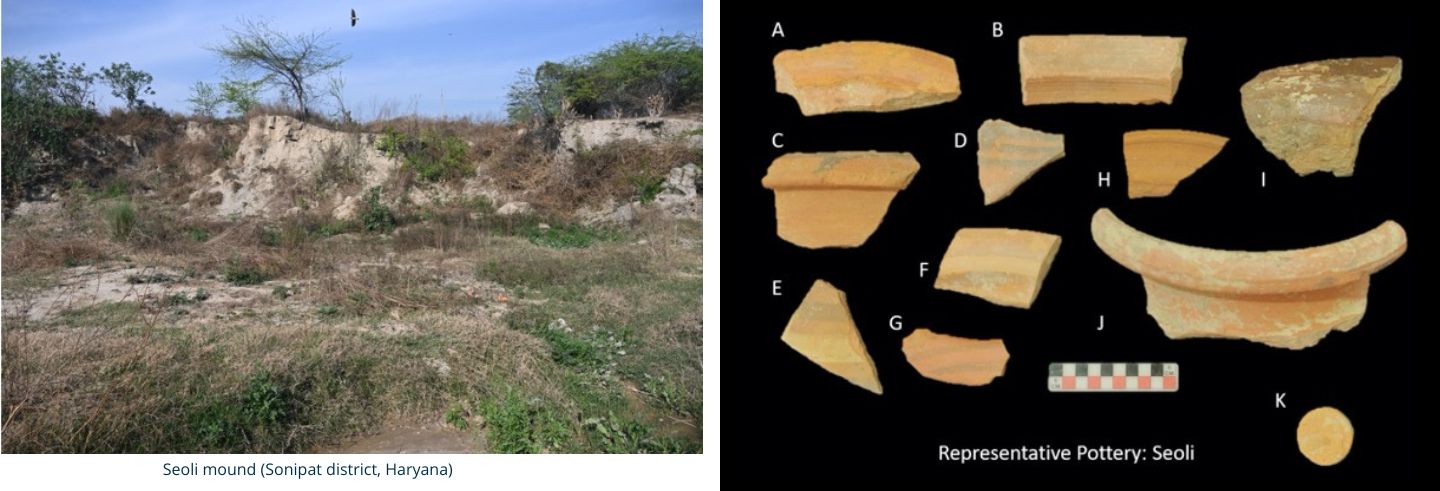

Seoli, some 3 kilometres from Ashoka University, is a village that is our university’s nearest neighborhood archaeological site. On the edge of Seoli, a mound known as Redaji (and also as Mahal) can be seen. One part of it is destroyed while the segment that has survived is entirely due to its its utility as a place for poop. There is a defecating ground here as also an area that is used for drying and storing cow dung. In the midst of this, what are the archaeological features that can be observed?

The mound itself has an elevation of 3 m at the highest point and is marked by a thick deposit. This may well be an accumulation created by wind-blown sediments. It is the surface of this natural high spot that was occupied by earlier settlers. There are red ware fragments and some with black paintings. Seoli seems to have been settled in medieval times. An earlier survey, though, did reveal early historic remains and that will be examined in future.

Archaeological relics in agricultural fields

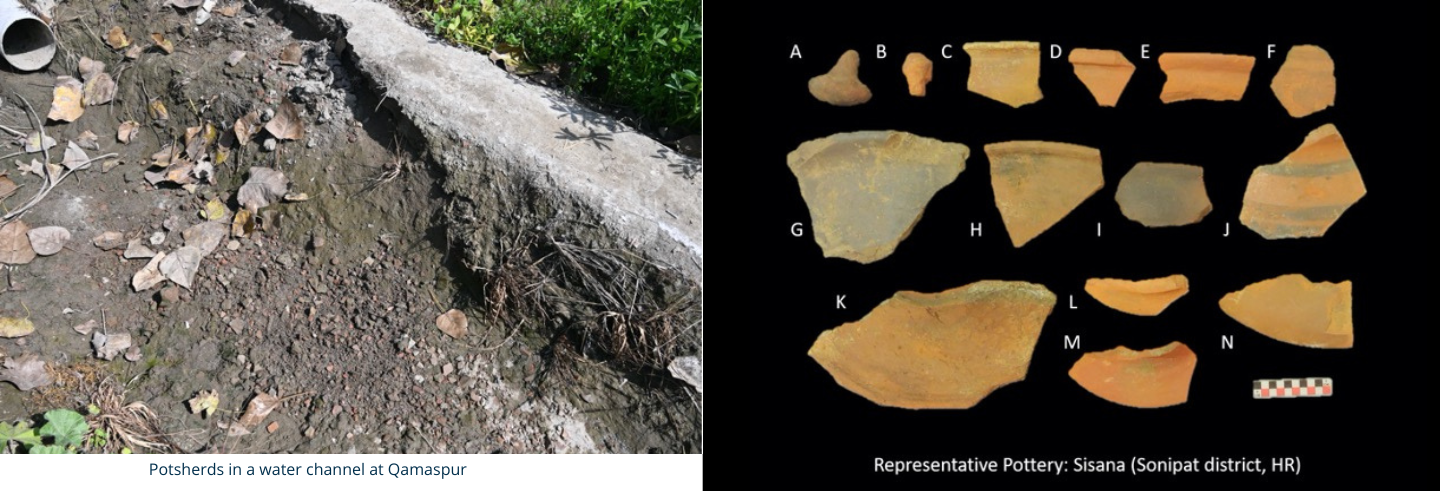

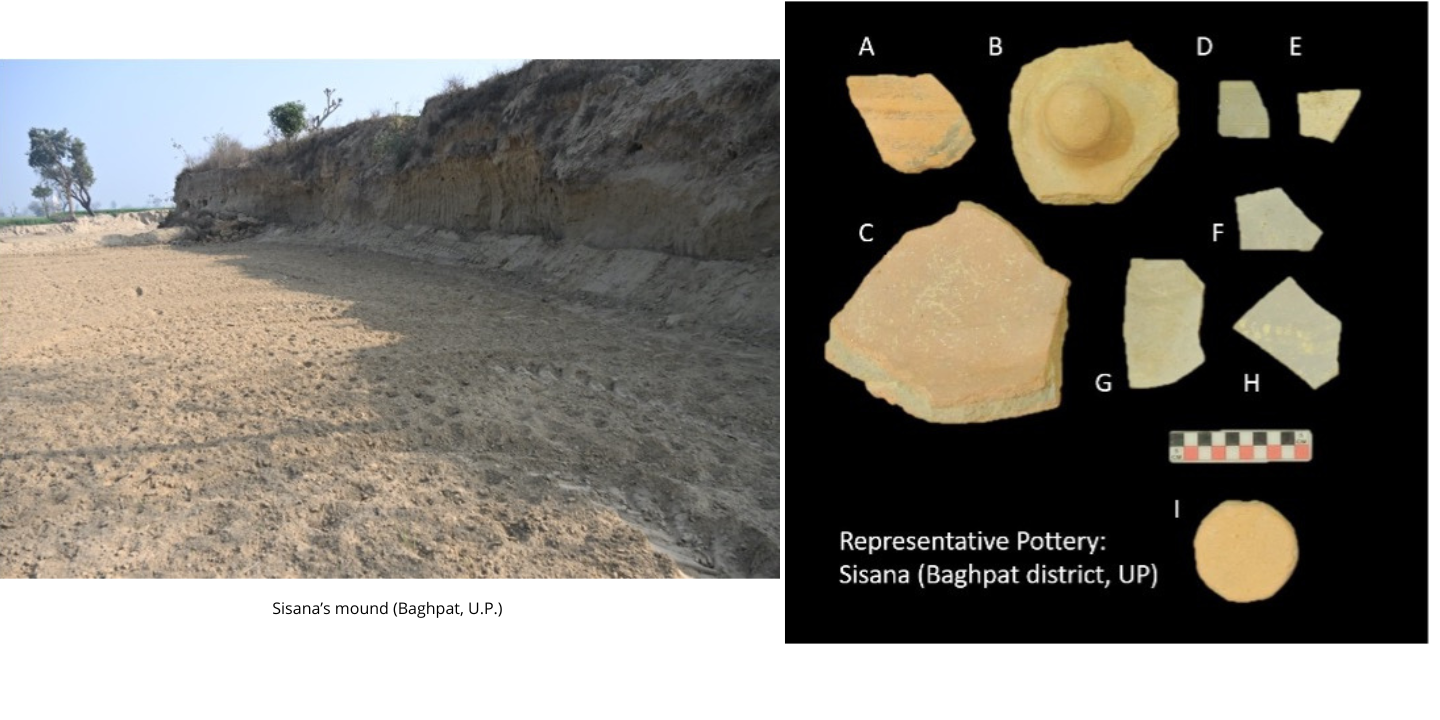

Not all old settlements in the Sonipat district have been as fortunate as Seoli. Two places, one on the edge of Qamaspur village and the other near Sisana no longer exist as mounds. These have been levelled and converted into fields. Qamaspur is about 5 kilometres from Ashoka University while Sisana is some 22 kms away. While Qamaspur lies in the active flood plain, Sisana is located on the older alluvium. Both, though, can today be recognized as places of premodern occupation only on the basis of the scatters of pottery there. In fields and in channels dug for irrigation, this is all that remains. The potsherds lie in fields and in fallow areas around them where they keep emerging because of ploughing and rainfall. Such pottery is also observed in dump-like clusters where irrigation water flows through channels.

Sisana’s ploughed up old settlement is known locally as Bijjal Kheda and is in the vicinity of a jaggery-making unit. The pottery here has a definite late Harappan influence with shapes like ‘dish-on-stand’ , some of which is likely to go back to the second millennium BCE. Some red pottery fragments have incised marks on them. A piece of iron slag was also found and some medieval pottery. This is evidently a spot where settlers for some three thousand years or so had lived but is now almost entirely eradicated.

The antiquity of the red ware in Qamaspur, not far from the Kalapad temple, is likely to be medieval. Is the name Kalapad (‘Kala-pahad’ or dark hill) an allusion to the mound that once stood in its vicinity? Who knows. What we know is that searching around for clues in the field makes many of us susceptible to believe in such stories.

Sonipat town - Old remains in new surroundings

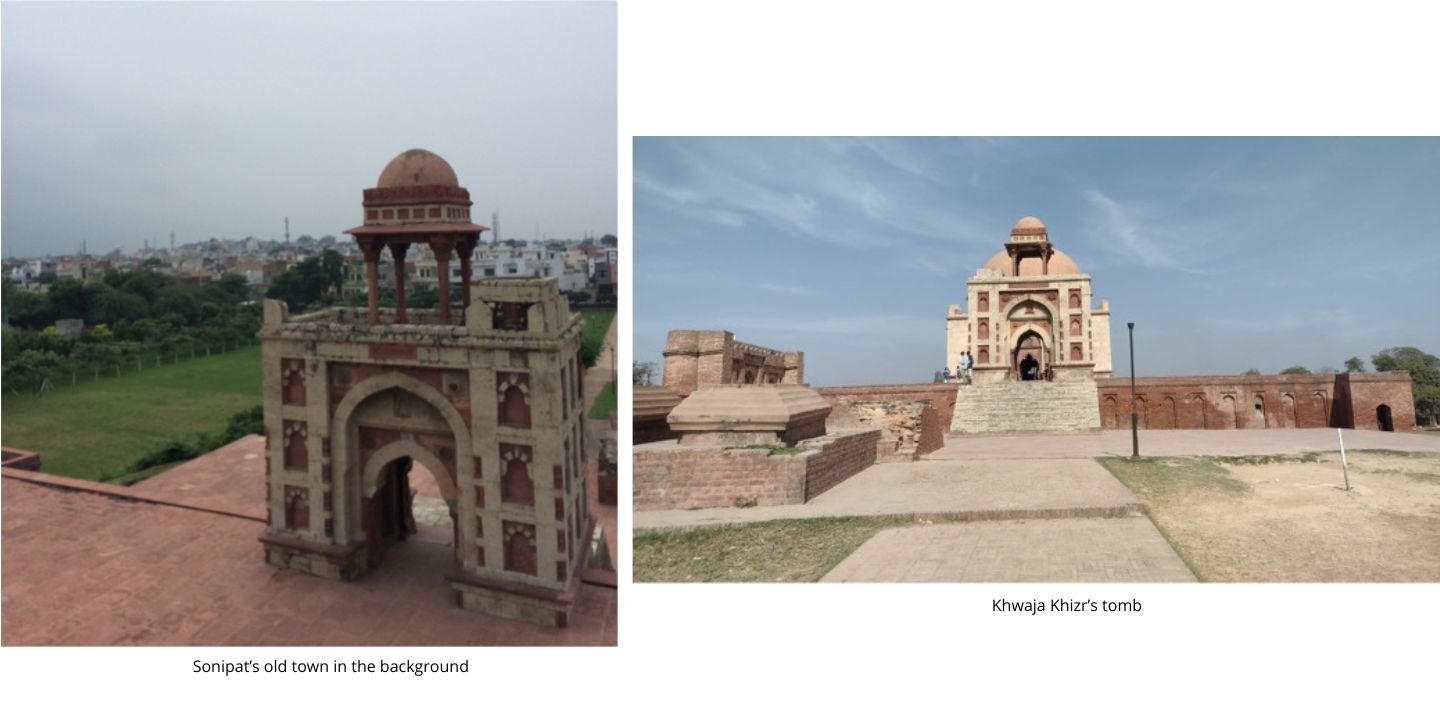

The town which gives this district its name is Sonipat. The name is derived from an older one, ‘Sonaprastha’, which was one of the five places demanded by the Pandava brothers from their Kaurava cousins in the Mahabharata story. The old town is marked by a very high mound. Its houses and shops, in fact, have colonized the mound, and a sense of this can be had as one goes through narrow lanes that wind up to the mound’s summit – from where one can get a panoramic view of the area. This eminence is visible on a clear day from Khwaja Khizr’s tomb which is at a distance from the town. The earliest pottery from the mound, as the 1955 work of B.B. Lal revealed, is painted grey ware.

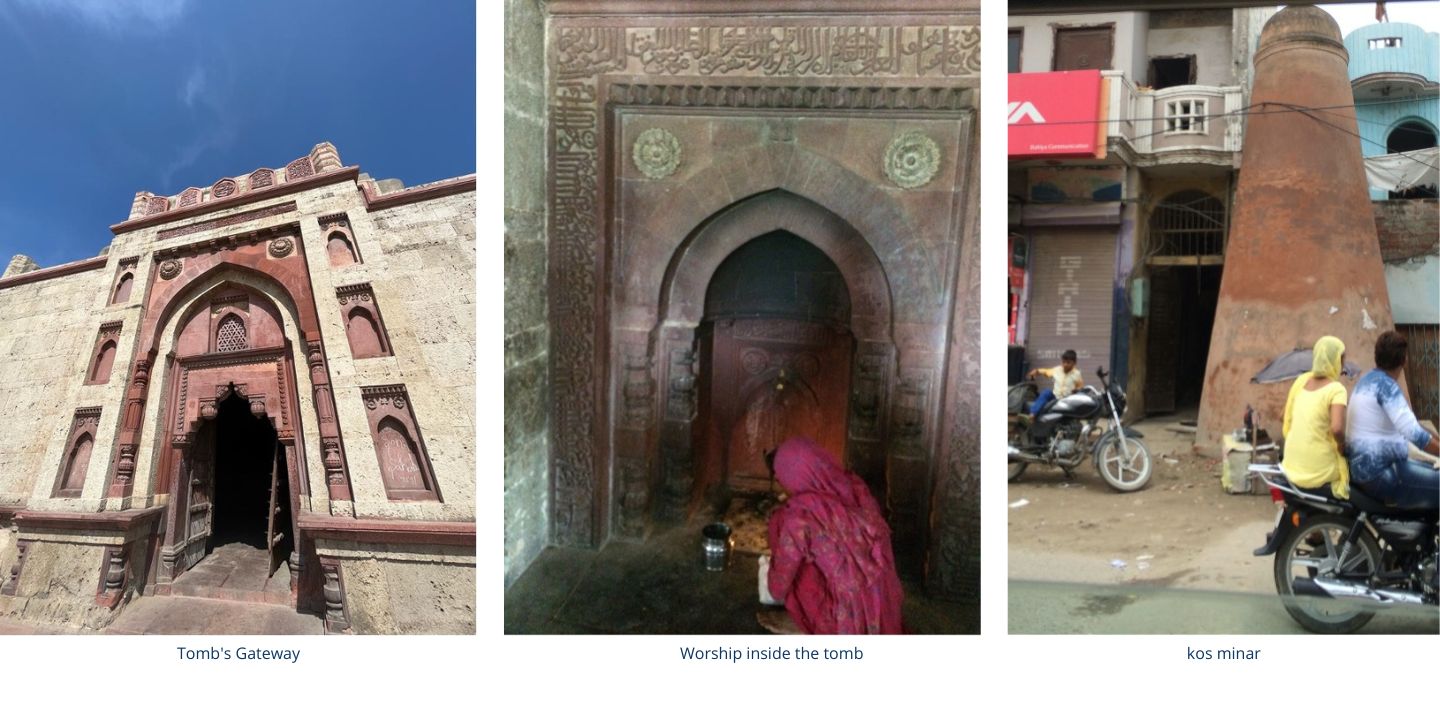

The sandstone tomb for Miyana Khwaja Khizr was built by Ibrahim Lodi in the 16th century. Kwaja Khizr was the son of Darya Khan Sarwani whose family had a lineage closely connected with northwest India (now Pakistan). So, the medieval history of Sonipat can be seen as extending far beyond rural Haryana. The tomb is actively worshipped and the first time when one of us visited it in 2016, the mother of an employee of Ashoka University had come to thank Khwaja Khizr who can be seen making an offering in a niche inside the tomb. This kind of worship is offered by people from many villages around Sonipat town.

The presence of ‘kos minars’ in Sonipat district – milestones put up by the Mughals – also underlines that the Grand Trunk road passed through this area. One such minar can be seen here, the brick structure rising from a broad base. Notwithstanding its significance, today it barely manages to make its presence felt in the midst of modern shops in Sonipat town.

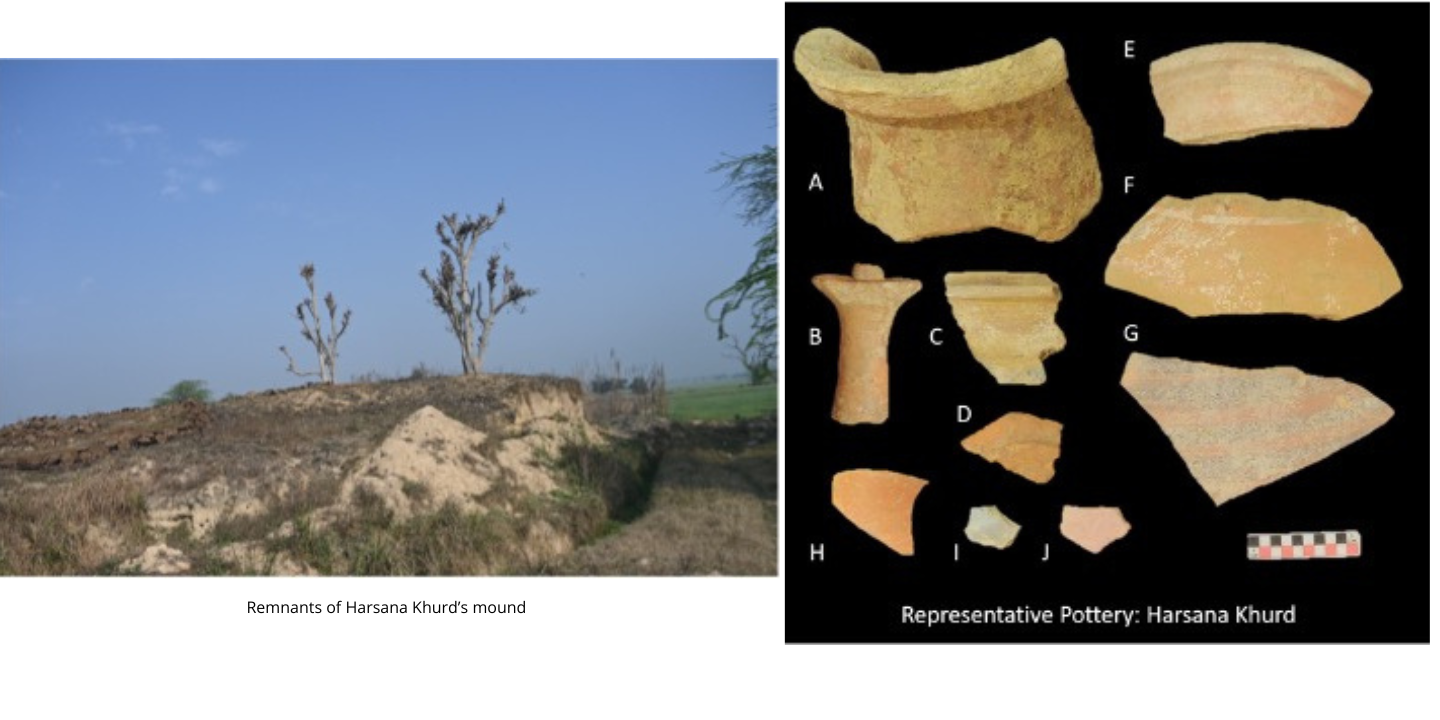

The area beyond Sonipat town is marked by many villages which are located on mounds, Harsana Kalan being one which we closely observed. Villages also have mounds in their vicinity. Harsana Khurd, very close to Harsana Kalan, has the remnants of a mound with red ware and grey ware which did not, however, have any diagnostic features. Chhatera too is marked by the small remnant of a mound in the midst of agricultural fields that have levelled large parts of it. A medieval well and fortifications were visible as also some grey and red ware fragments.

Crossing the Yamuna river

If the mound in Sonipat district’s Sisana no longer exists, another Sisana in Baghpat district has fared much better. This Sisana is some ten kilometres from Ashoka University, and not far from the Yamuna river. Today, the river is some two kilometres from there, but it is likely to have been much closer to it in ancient times. Like Seoli, the site is located on the top of a 10 m high natural elevation. This could be either riverine or aeolian and has been cut up in various places to create arable land. Many parts, though, are still preserved and visible as high grounds fringing the fields. Calcrete concretions are occasionally visible in the mound areas, with evidence of collapse and talus in the exposed section profiles.

The southern part of the surviving mound had more significant pottery scatters with grey ware, red ware and black-slipped ware. Much of this would go back to the first millennium BCE when grey pottery was common. The typical pottery which allows grey wares to be securely placed in the early first millennium BCE is marked by paintings (and, is thus, appropriately called painted grey ware). Some fragments have been found at Sisana.

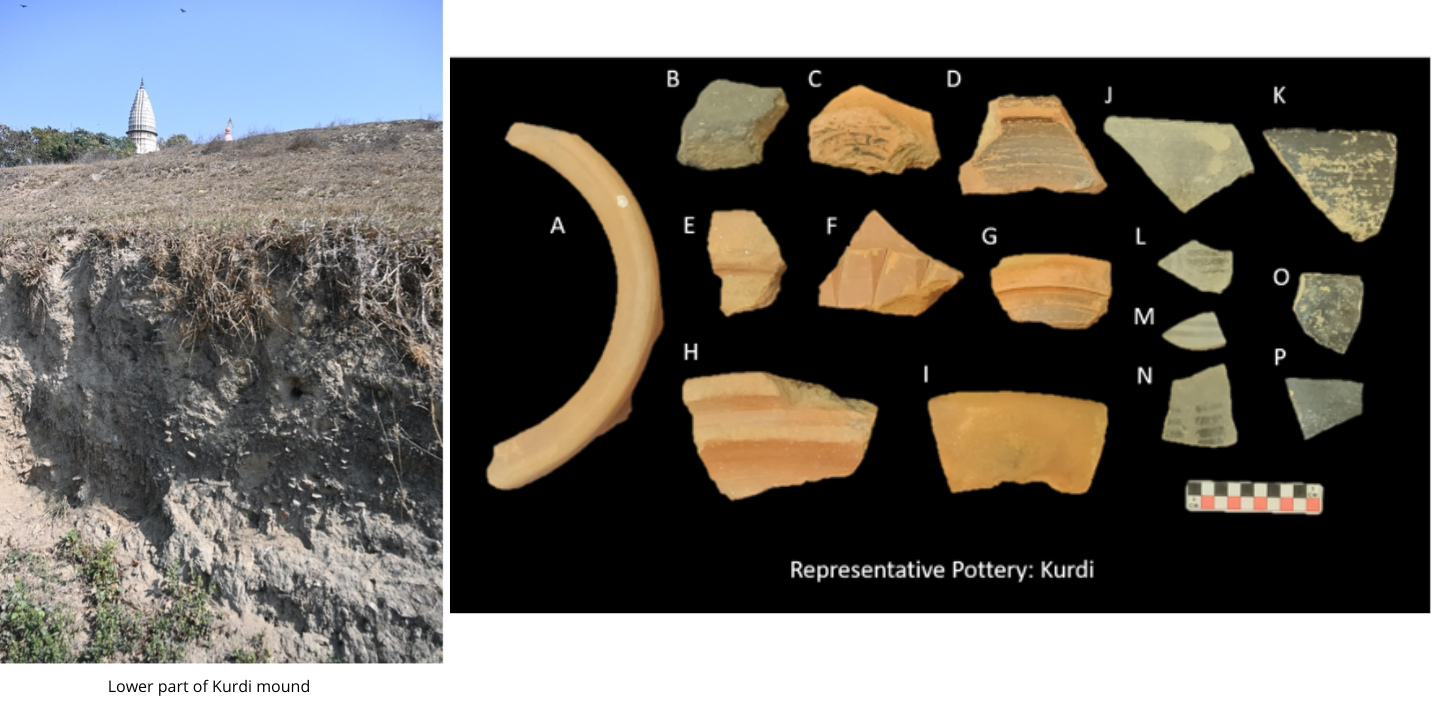

At Kurdi, two kilometres from the eastern bank of the Yamuna, such painted pottery fragments in significant quantity can be observed. The Kurdi mound is high and fairly intact, standing some 15 m above the surrounding plains. Because of the presence of a Shiva temple, its local name is Shiva Mandir Tila. The painted grey ware can be seen quite commonly in the lower part of the mound, with fragments marked by linear patterns in black. There was also red ware, grey ware, black slipped ware, corded ware and a red pottery that is usually found in historic times. Bricks too (of the early centuries CE) lie scattered in some rain gullies that feed into a seasonal stream in its vicinity.

Considering that this is not far from Sinauli where excavations conducted by the ASI yielded spectacular second millennium BCE remains (including those of a chariot), it is possible that there are cultural remains below the painted grey ware deposit here. Only a trial excavation here would be able to settle this but as things stand, this is a mound where a palimpsest of cultures in layers – from the ancient to the medieval – is most likely to be uncovered.

How has the Yamuna river changed over the centuries? How did the elevations in the alluvial plains where sites are often located get created? What are the other fields and fallows in this belt that bear markers of settlements that have disappeared?2 These are questions that will be taken up in the future. Hopefully, what has been set out here provides some glimmerings of the rich history that lies scattered in the surroundings of Ashoka university.

Location of archaeological sites investigated during the course of reconnaissance fieldwork in February 2023

The Team

- The team was made up of Nayanjot Lahiri (Ashoka University), Rakesh Tiwari (ex-director general, Archaeological Survey of India), Akash Srinivas (Ashoka University), and Harshdev Tomar (Central University of Haryana). The following members of Ashoka University also accompanied the team on various days: Kalyan Sekhar Chakraborty, Kritika Garg, Samayita Banerjee, Debdutta Sanyal and Aneesh Sriram. The photographs of pottery and the preliminary report was done by Akash Srinivas. Two photographs of Khawja Khizr were taken by Debdutta Sanyal and Samayita Banerjee. Other photographs were provided by Nayanjot Lahiri.

- To begin with, this can be done by revisiting the sites mentioned in Silak Ram. 1972. Archaeology of Rohtak and Hisar Districts (Haryana) Ph.D. Thesis, Kurukshetra University. Also R.C. Thakran.2009. Dynamics of Settlement Archaeology (Haryana) . New Delhi: Gyan Publishing House.