The Spirit of Conservation: the Case of Mangar Bani

By Jatin Abhir

Introduction: the Spirit of Conservation

At the intersection of the modern political boundaries of Faridabad, Gurugram and Delhi, lies a forested landscape whose history reveals a remarkable intersection of community, conservation, corporations and states. The place is Mangar Bani, a micro-habitat of tropical deciduous forests on the Delhi Ridge. As one of the last remaining natural forests close to Delhi, it is, notes the environmentalist Pradip Krishen, a sample of what the Delhi Ridge could have looked like before extensive resource exploitation.1 Mangar and its surroundings harbour diverse wildlife – more than thirty species of trees, some of which have gone extinct elsewhere in Delhi; fauna ranging from leopards and hyenas to nilgais and langurs; and perhaps more than two hundred species of birds.2

The very existence of Mangar Bani close to three rapidly expanding metropolises, mining and grazing resources, would not have been possible without the prevalent opinion in the surrounding villages that the woods are sacred. Folklore from the villages informs us that a certain holy man, Gudariyadas Baba, who also has a temple dedicated to him in the forest, once resided here. His spirit is believed to defend any harm to the forest, by meting out divine punishments of varying degrees, including untimely death!3 This centuries-long, community-enforced (and later panchayat-enforced) prohibition on unsustainable activities in the forest ultimately resulted in the long-term preservation of the forest, but in the last two decades, the arena of its conservation has shifted from panchayats to courtrooms and activists’ essays. This is because the new looming threat to Mangar Bani is not local individuals but corporations and policymakers, who come armed with bulldozers, development blueprints and land deeds.

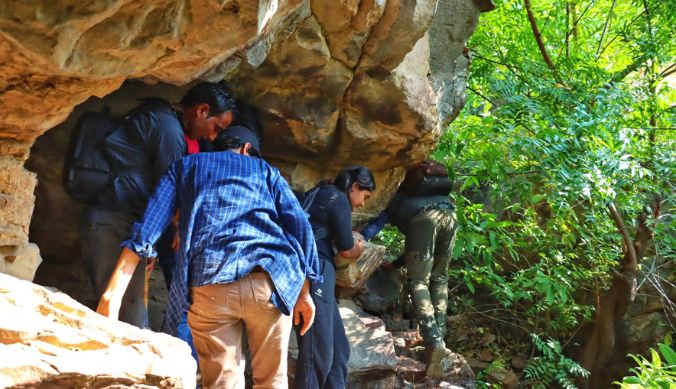

Approaching Mangar Bani

Credits: Author.

On 21st October 2023, a field trip to Mangar Bani was organised for students enrolled in the courses The Jungle, the Spade and the Book and Archaeology and Science. This fieldwork was intended to introduce us to the kind of evidence one can encounter while attempting to write a history of forests and wilderness. The group was led by Prof. Nayanjot Lahiri, and upon reaching the forest, we were joined by forest researchers Chetan Agarwal and Sunil Harsana, the latter of whom was born and raised in Mangar, a village adjacent to the sacred forest. Both of them have for decades laboured to defend Mangar from corporate encroachment and have extensively documented the flora and fauna of the region.

Entering a forested space after crossing the entire length of Delhi is bound to inspire the idea of contrast. As Aneesh, one of my fellow coursemates remarked, “amidst the concrete jungles of the National Capital Region, it is remarkable that one can witness an ecological enclave of such lush greenery. Equally, Mangar can be an important region to explore the field of landscape archaeology, helping us to establish a relationship between the hills, the forests and the people, as it has evidence ranging from Palaeolithic stone tools to Gupta-Kushana pottery.”4 For both archaeologists and geologists, it would be useful to zoom out of Mangar and consider the Delhi Ridge’s physical structure, for a lot of new answers and questions about Mangar would arise from understanding Mangar as a part of the Ridge and the Ridge as a part of the Aravallis. If the landscape of Mangar can be read as a text, its context lies in the Ridge.

The Aravallis and the Delhi Ridge

The Aravallis are one of the oldest geological structures on Earth, and they run from Gujarat to Rajasthan to Delhi. Recent scholarship on the archaeology of the Ridge has emphasised the need to shift our focus from sites to landscapes, given the nature of evidence like stone tools, which are usually found scattered on the surface.5 Observing the distribution of stone tools across the landscape can allow us to see the residential preferences of prehistoric groups living on the Ridge. For instance, the prehistoric makers of microliths who lived in the region seem to have preferred settling on hills or along the edges of ravines, which permitted a clear view of the landscape.6 More intensive research on the ridge needs to be done before we notice the implications of such patterns. As of now, we do know that the Ridge is a high-yielding region in terms of both prehistoric and historic surface artefacts, though rapid urbanisation has also resulted in the rapid destruction of such surface evidence. For example, in 1985-86, a survey for prehistoric evidence found 43 Stone Age sites in the Aravallis of Delhi and Haryana.7 Similarly, ten years later, in 1994-95, a survey for protohistoric and historic sites yielded fifty new sites from just the Ballabgarh tehsil of Faridabad. The survey also revealed that the drainage zones of rivers were the preferred areas of habitation and building of shrines—an evidence useful for landscape archaeology.8

However, it was not only the prehistoric and early historic residents of the Ridge that showed strategic and aesthetic love for the hills and plateaux of Delhi. For instance, in medieval Delhi, both Delhi Sultans and the rebel polities opposing them preferred capitals, fortifications and refuges on the Ridge’s outcrops. Centuries later, when Viceroy Charles Hardinge was choosing a site for imperial New Delhi’s Government House, he chose Raisina, because “from the top of the hill, there was a magnificent view embracing Old Delhi, and all of the principal monuments situated outside the town, with the River at a little distance.”9 Millennia ago, the dwellers of the Ridge perhaps thought something similar to themselves – this place permits a panoramic view of the landscape below and access to seasonal streams draining the ridges, so let us reside here!

Keeping in mind this context of the long history of human settlements on the Ridge, we can now continue our journey to Mangar Bani.

The Experience of Mangar Bani

As one crosses Mangar village and descends into the valley surrounded by eroded Aravallis, one encounters multiple rocky outcrops. The Dhau tree dominates the foliage, and depending on the season, the hills are either lush green or woody brown. Slowly, we trekked up a rocky path up the hills until we reached spots where cupules (significance unknown), geometric patterns (board games?) and rock paintings (religious symbols?) have been found. Harsana was the first one to identify these remains as historically significant. As Maitreya recalled, “The efforts of Sunil Harsana were eye-opening to me. He has done commendable work in trying to protect Mangar, and his deep knowledge of the place made it possible for us to find the remains on top of the cliff. We can learn grassroots environmental and historical engagement from people like him.”10 Other material evidence from the vicinity includes scattered potsherds and stone tools. Some of the potsherds are stylistically from the Kushana period of the early centuries CE, while the stone tools can be stylistically dated to the Lower Palaeolithic period.

Credits: Author.

It needs to be emphasised, however, that no scientific dating has been done on these archaeological remains, and thus the chronology of the remains, including the rock art, is unknown. The rock paintings have survived in a small rock-shelter-like feature. To reach the shelter, one needs to carefully descend along a gully and then step into the shelter (hoping not to encounter a leopard since they have been reported to spend time in the shelter at times)! While extensive research is required before we can say anything with surety about the history of Mangar in prehistoric and historic periods, the diversity of evidence is promising. As Twisha observed, “We witnessed how this relatively untouched part of the Aravallis had preserved an extensive chunk of history and wildlife. It’s a testament to the deep and enduring connection between humans and nature over the course of history.”11

The geographical position of archaeological finds, plotted using GPS coordinates on Google Earth. The starting point of the field trek can be seen on the bottom left of the image. In the top left is Mangar Bani, the sacred forest.

Credits: Samayita Banerjee.

Credits: Author.

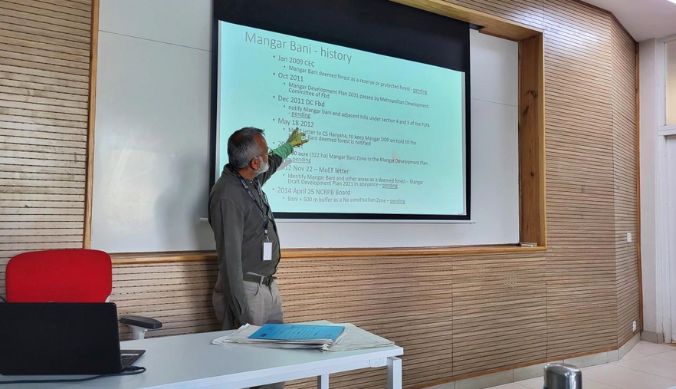

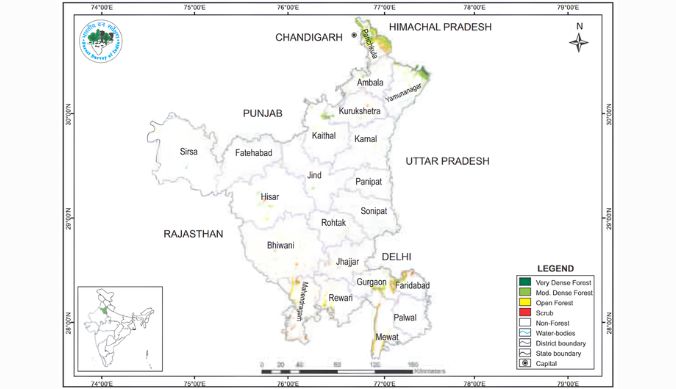

Temporary Gains, Permanent Losses: the Legal Battles in Defence of Mangar Bani

As of 2019, Haryana had less than 4% of its geographical area categorised as forests of any kind, and a rather minuscule 0.06% as very dense forest.12 Given this context, the neglect of Mangar Bani is worrying. In the last two decades, Mangar Bani has increasingly come under stress. The forest covers no less than 4,200 acres of land, but the law grants protected status only to around 1,600 acres of it, out of which a thousand acres is the buffer zone.13 Chetan Agarwal has worked on the legal history of Mangar, and he joined us once again, this time as a guest lecturer for the course The Jungle, the Spade and the Book, a week and a half after the field trip.

At the moment Mangar Bani is categorised as a “no construction zone” in the law books. However, judging by its previous legal history, when its status constantly oscillated between protected and unprotected land, one cannot say how durable the present status is.14 Observing the fluctuating fortunes of Mangar Bani and the tendency of deforestation to be irreversible, one of Agarwal’s economist friends once quipped that “all gains are temporary and all losses are permanent,” for activists working for conserving forests.15 For example, the radius of the buffer zone around the forest was once reduced from 500 to 60 metres and then back to 500 metres within a period of less than two years.16 Even short-term changes in the status and size of the buffer zone like this can potentially pave the way for the commencement of construction activities close to the forest – permanent losses that can occur within temporary oscillations of zoning policies. It is only due to the eternal vigilance of the locals and activists that Mangar has escaped the worst to this day.

The locals’ long-term commitment to the forest contrasts well with the state’s temporary and half-hearted commitment to its preservation. The ambiguous legal status of the forest is a constant threat to its security. For instance, corporate purchases of land were permitted in the core zone in 2005, which opened doors for the state government to claim in 2012 that since Mangar was private property, forest conservation laws would not apply to it. This was followed by hundreds of villagers signing letters of protest, in a movement led by the Gram Vikas Samiti. The plea finally reached the desks of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, the Prime Minister’s Office and the High Court, all of whom decided in favour of the villagers in 2014.17

Conclusion: Reforesting the Narratives of the Past

In its growth, as in its loss, Mangar Bani has depended on powerful political ideas. Whether it is the power of a forest spirit to inspire reverence towards it, or the logic of capital that inspires inroads into the region for the purpose of “development,” Mangar Bani is a stark reminder of how different ideological concerns, or different ways of seeing the same forest, can end up producing vastly different results on our material world. The idea of sacred space has worked effectively for Mangar Bani – but we have yet to witness external players who shape the fate of the forest share the same urge for preservation as the locals do.

Indeed, the urge to preserve may be expressed in different idioms and ideas. It can be divinity and livelihood for villagers living around the forest; it can be social justice and natural capital for the ministries of environment; it can be aesthetics of ecology and enjoyment of natural beauty for tourists; or it can be preservation of rock art and artefacts for scholars. Or it can be all of them at once. But it has to be something. We cannot erase the environment and forests from our political imaginary and expect preservation. Because the inhabitants around Mangar Bani held onto their imaginary of the forest and granted it both an inherent and instrumental value, this forest survived models of development presently in effect around it. Otherwise, it too could have joined the ranks of the casualties of an urbanising world.

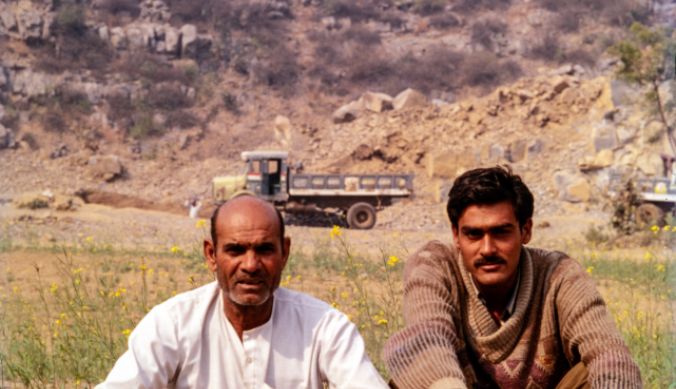

Credits: Nayanjot Lahiri.

State planning would benefit from introducing the environment not as an expendable margin, but as a central consideration in policy. Likewise, scholarship, especially archaeological scholarship on historical India, can benefit from shifting the gaze from cities, settlements and empires to forests and wilderness.18 Mangar Bani is a case that expands our understanding on both these fronts. The premodern evidence it holds can allow us to reconstruct human-environment interactions in past societies living on the Ridge. It is a reminder that historical culture and settlements also need to be looked for under rock shelters and forest canopies as much as they need to be looked for in mounds and around towns and villages. Reforesting the narratives of the past, that is. On the other end, the modern history of Mangar Bani reminds us about the consequences of forgetting about forests in our contemporary imagination; though it also gives some solace, since at least this forest has found its tireless defenders that have reasoned the state down the path of valuing and protecting the forest.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to Prof. Nayanjot Lahiri for her comments on the drafts of this essay, and for providing older photographs of Mangar from the year 1994-95.

Appendix

Credits: The Forest Survey of India.

Credits: Nayanjot Lahiri.

Credits: Nayanjot Lahiri.

Credits: Author.

Credits: Aneesh Sriram.

(The report is written by Jatin Abhir, a student of the Ashoka Scholars Programme, from the batch of 2024 at Ashoka University)

Endnotes

- Pradip Krishen, The Trees of Delhi (New Delhi: Dorling Kindersley, 2006), 25.

- Chetan Agarwal, “Mangar Bani and Other Forests,” Sanctuary Asia 40, no. 2 (February 2020). https://sanctuarynaturefoundation.org/article/mangar-bani-and-other-forests; Krishen, Trees of Delhi, 25-26

- Chetan Agarwal, “Who Owns, Who Zones, Mangar Bani?” Land Art, Visual Art Gallery, India Habitat Centre (2017).

- Aneesh Sriram, personal communication, November 2023.

- Mudit Trivedi, “On the Surface, Things Appear to be…: Perspectives on the Archaeology of the Delhi Ridge,” in Ancient India: New Research, eds. Upinder Singh and Nayanjot Lahiri (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009), 40.

- Upinder Singh and Nayanjot Lahiri, “Introduction,” in Ancient India: New Research, eds. Upinder Singh and Nayanjot Lahiri (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2009), 3-4.

- Dilip K. Chakrabarti and Nayanjot Lahiri, “A Preliminary Report on the Stone Age of the Union Territory of Delhi and Haryana,” in Delhi: Ancient History, ed. Upinder Singh (New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2006), 7.

- Nayanjot Lahiri, Upinder Singh and Tarika Uberoi, “Preliminary Field Report on the Archaeology of Faridabad – the Ballabgarh tehsil,” Man and Environment XXI no. 1 (1996): 56.

- Quoted in Nayanjot Lahiri, “On the Rocks,” Namaste: The ITC Hotels Magazine (2015): 43.

- Maitreya Sukumar, personal communication, November 2023.

- Twisha Sangwan, personal communication, November 2023.

- The Forest Survey of India, Indian State of Forest Report 2019, 83. https://fsi.nic.in/isfr19/vol2/isfr-2019-vol-ii-haryana.pdf

- Agarwal, “Who Owns, Who Zones, Mangar Bani?” Agarwal, “Mangar Bani and Other Forests.”

- Agarwal, “Who Owns, Who Zones, Mangar Bani?”

- Chetan Agarwal, personal communication during lecture, November 2023.

- Agarwal, “Who Owns, Who Zones, Mangar Bani?”

- Agarwal, “Who Owns, Who Zones, Mangar Bani?”

- Nayanjot Lahiri, M. B. Rajani, Debdutta Sanyal, Samayita Banerjee and Satyendra Tiwari, “Tracing Ancient Itinerants and Early Medieval Rulers in the forests of Bandhavgarh,” South Asian Studies 2023: 1.

- The photograph is taken from the essay by Agarwal, “Mangar Bani and Other Forests.”